3. February 2017

The demands on organisations are growing steadily, while the private and business world is becoming more complex and increasingly less predictable. As the recent past has clearly shown, we are challenged daily by issues which are always good for surprises: not only digitalisation as one of the big drivers, but also other trends, such as urbanisation, progressive globalisation, environmental issues and political developments.

Many companies are rather ill-prepared for these developments and do not adequately use their own potential or the knowledge of employees who are, in fact, highly qualified. Very often, they continue with previously successful behaviour and react to new requirements with known patterns. Above all, management still largely uses methods which originated in the industrial age and are often not suited to meet the new requirements. Although the insight is fundamentally there and this is repeatedly confirmed at many of the countless conferences, in reality, little has changed so far, and if so, then rather slowly.

Why is that? Why is this existing knowledge not translated to the extent necessary? The answer is relatively simple: classical management principles have been successful in the old world for many decades. To replace or change them would mean entering upon unknown terrain and taking a risk. This leads to great uncertainty, particularly for organisations that have grown over many years. After all, there is an existing business that should not be placed in danger. Where and how do we start?

Experience shows that either detailed knowledge about the condition of one’s own organisation is very often lacking, or the assessments and pictures diverge considerably at the upper management level. Often, there is also a lack of information regarding where a successful intervention can be put in place, or there are negative experiences with change projects which are rather ineffective in the end. Management development, insofar as it exists as a solid element, often fails to achieve the desired effect, which is then a clear signal for missed or inadequate implementation measures. Causes and connections between these often observed effects are complex and mostly not obvious at first sight.

In an increasingly dynamic (VUCA-) environment, where corporate management is becoming more and more demanding, established recipes and procedures, which are often still based on stable and (therefore) more predictable times, are rather bad. Or they are completely ineffective because they provide the wrong answers to current challenges.

A typical example of this is the still-widespread instrument of management by objectives (MbO). Targets have often already been surpassed when they are agreed upon or, after a short time, they no longer fit into the changed requirements of the business. New developments that arise asynchronously, i.e. within the target period, cannot be addressed appropriately if they do not match the previously agreed targets, which often leads to a lack of resources, budget, etc. Moreover, a consistent goal development of the individual employee often leads to the self-optimisation of the individual rather than the company (division).

Effects such as these are numerous; They often establish themselves over years, creep unwittingly and unintentionally as increasingly larger disturbances against the backdrop of a changing environment and ultimately become manifested as part of an enterprise culture. Changing this is extremely difficult and ultimately only possible through a changed management.

Leaders have the responsibility of creating an environment with as few disturbances as possible so that peak performance can be achieved. The most important first step is the development of precise knowledge about the nature and effect of these »disturbances« through a complete and comprehensive analysis of the status quo. In order to make such an analysis meaningful, a comprehensive (management) model is needed which takes into account the most important aspects and their interactions within the company context.

The performance triangle, developed over years by Lukas Michel and his worldwide Agility Insights-Netzwerk, is such a scientifically based model that creates a bridge between the skills of people and the challenges of organisations.

The performance triangle, developed over years by Lukas Michel and his worldwide Agility Insights-Netzwerk, is such a scientifically based model that creates a bridge between the skills of people and the challenges of organisations.

The core idea is to identify future organisational skills at an early stage so that the necessary talent, teams and structures can be developed.

People with their talents and abilities are the heart of the triangle. In the sense that »self-responsibility is an essential foundation for knowledge, work and motivation« (Peter F. Drucker) and that »trust leads« (Reinhard K. Sprenger), this promotes the speed in organisations through competent decisions on the customer front, the use of the knowledge of capable employees and management that primarily acts as an enabler.

Culture, leadership and systems form the corners of the triangle. Good decisions and effective actions require a culture that creates a common context. Management has to actively promote dialogue and interaction via purpose, orientation and performance. Systems have to work diagnostically to draw attention to what is important and to make corrections possible at any time. Intensive interactions and diagnostic control are fundamental abilities of agile organisations, since they enable early detection and interpretation of signals and corresponding actions.

Above all, in addition to knowledge, what is required for good decisions by people is purpose, which is at the same time a decisive basis for intrinsic motivation. Internal and external relationships help to continually develop and exchange this knowledge and to utilise it as added value for the customer. Combined knowledge, the collective experience and the shared benefit from it allow new developments and promote innovative power. Purpose, co-operation and relationships are the organisational skills that help to be able to absorb the shock of unexpected external shocks and influences. They are the sides that hold together the triangle of culture, leadership and systems.

Via speed, agility and resilience, the performance triangle leads to the ability to take action. Organisations with these skills use the knowledge in the networks of employees while at the same time creating the organisational skills to deal with the dynamics of the environment as effectively as possible.

Companies with an effective management that actively shapes their own organisation for their (knowledge) employees and places people at the centre have the potential to emerge as winners of the new era.

Diagnostic mentoring is the process that allows the systematic development of these dynamic skills. It is based on 3 steps:

- Decoding

Analysis of the existing capabilities by comprehensive diagnostics and benchmarking (on-line tool)

- Designing

Creating the target image of the future organisational skills (CEO briefing and executive team workshops)

- Development

Creating change steps and their implementation via the performance triangle with the involvement of the operative organisation (mentoring and day workshops)

Even if there is a wealth of tools and support from specially trained mentors from the Agility Insights network, this further development for the affected companies always involves a transformation that fundamentally changes behaviour and competencies, puts existing issues into question, interferes with established processes and, therefore, always involves risks.

A fundamental development affects decision-making competences. Within the scope of further development, managers have to decide

- How they want to involve or incorporate employees

- How work is to be coordinated and guided

- How goals are set and pursued

- How changes/adaptations are made

- How decisions are made

For each of these 5 key questions, it is necessary to select and establish either

a) more self-responsibility on the part of employees or

b) control by the executive management.

Depending on the combination of the answers, different concepts for the management and the organisation arise.

This »work on the system«, the correct design of leadership and organisation, is not a task for the workforce or the lower and middle management. It cannot be delegated, but rather has to begin at the top of an organisation in the executive team.

In the beginning, a clean diagnosis, analysis and interpretation of the results as well as consensus responses to the five principle questions mentioned above are performed. Only then does the concretisation in the different functional areas of the organisation and the formulation of precise interventions begin.

It is and remains the responsibility of the executive management to decide how to address the necessary changes in order to activate the potential and implement it for the benefit of the organisation, the customers and the business.

Rüdiger Schönbohm

TYSCON Management Consulting & Business Partner Agility Insights

Pictures and individual text passages

© Agility Insights AG, 2016 / Cover picture: Pixabay

3. February 2017

The book »Anders wirtschaften – Integrale Impulse für eine plurale Ökomomie« (Economising Differently – Integral Impulses for a Plural Ecomomy) provides an approach to achieve a systemic understanding of corporate organisation and leadership.

On Tuesday, 10 January 2017, an approximately 30-member guest group, including a diverse mixture from the start-up scene and entrepreneurs, business angels as well as representatives of institutes and universities, expressed lively interest with enthusiastic discussion of the presented topic. One thing crystallised at the event organised by the Berlin Project Centre of the Wuppertal Instituts für Klima, Umwelt, Energie (climate, environment and energy) (in the three lectures regarding the book topics as well as in the ensuing discussion and the ever-changing conversations in the subsequent Get together): A world in upheaval needs thinkers and implementers who are open to upheaval and risk.

The co-editor of the book »Anders wirtschaften«, the consultant and developer of organisations and leadership personalities Jens Hollmann, summarised the challenge for organisations and their leaders in the following perceptive statement:

»There is a kind of risk that, if not taken, incapacitates us.«

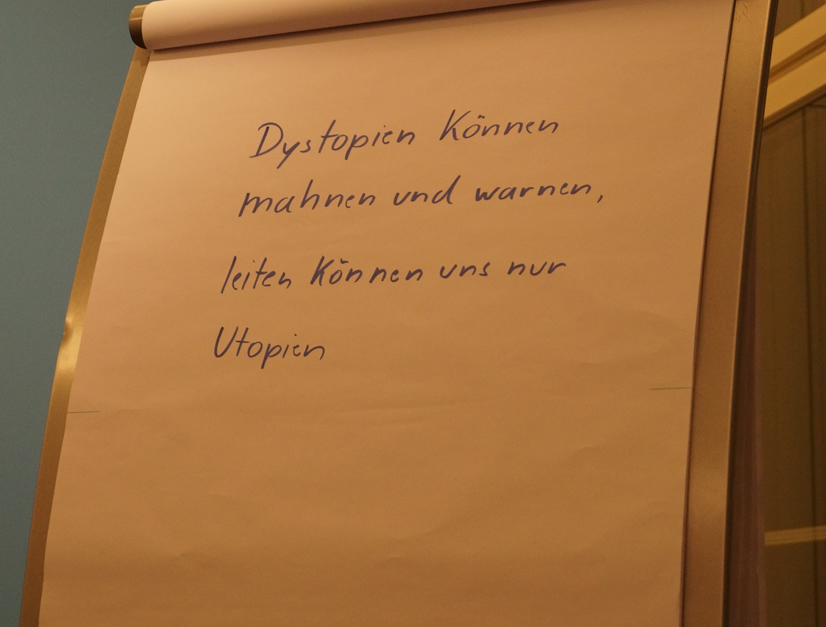

Anyone who, in a world of increasing diversity and the resulting diverse but contradictory challenges, where more facets of complexity are becoming perceptible, and in which developments surpass themselves – anyone in such a world for which the attribute »complicated« is too narrow and oversimplified, looks away, trusting in familiar solutions – this person will no longer play a role tomorrow. And it is not the dystopias, the negative scenarios in a world which is no longer comprehensible that enable us to mature for the future. According to Hollmann, the utopias that project scenarios, their possible achievement and the associated risks, such as those of failure, are more than justified. Particularly since failure opens the door to further options and evokes an awareness of success.

Prof. Uwe Schneidewind, President of the Wuppertal Institute (WI) and co-author of the book »Anders wirtschaften«, illustrates the social change in consciousness in its trinity of social, economic and ecological relevance that characterises our present and particularly , the forecasted future.

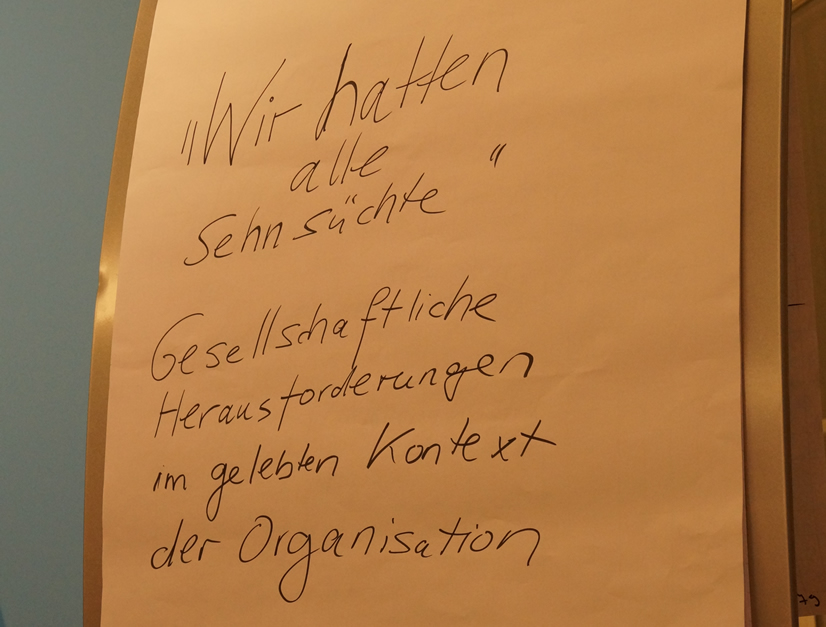

»We all had aspirations«

In her contribution »Wir hatten alle Sehnsüchte« [we all had aspirations], the communication consultant Katharina Daniels, co-editor and author of the book »Anders wirtschaften«, explains a quotation which is borrowed from a transformation process in a traditional German company in which there are no longer any classic organisational charts and hierarchies and in which all the actors in the company – from the strategic level to the employee at the machine – are (mutually) responsible for the success of their company in their roles and functions.

How models are reanimated

There are models that support and promote such a change in consciousness within the organisation, such as the »Urban Gardening« of the consulting firm SYNNECTA, in which the employee communities that are non-existent in the organisational chart are discovered and integrated – or »Holacracy« (the corporate operating system stemming from the American economy), with its shift from personal hierarchy to task-related responsibility. Or the Compass for Collective Leadership, which, in complex projects, unveils six awareness and leadership skills that pave the way for transparency and the sharing of responsibility for the benefit of collaborative projects.

26. June 2015

It is the early 1800s. The British warship HMS Surprise is about to engage the enemy. The crew are all preparing below deck. The portholeopens and the captain climbs down in order to commit his men to the sea battle with the French privateer Acheron:

It is the early 1800s. The British warship HMS Surprise is about to engage the enemy. The crew are all preparing below deck. The portholeopens and the captain climbs down in order to commit his men to the sea battle with the French privateer Acheron:

»Right lads (…)! (…) discipline will count just as much as courage. The Acheron is a tough nut to crack: more than twice our guns, more than twice our numbers, and they will sell their lives dearly. Topmen, your handling of the sheets to be lubberly and un-navy like. Until the signal calls, you’re to spill the wind from our sails, this will bring us almost to a complete stop. Gun crews, you must run out and tie down in double quick time. With the rear wheels removed, you’ve gained elevation. And without recoil, there’ll be no chance for re-load, so gun captains, that gives you one shot from the lardboard battery … one shot only. You’ll fire for her mainmast. Much will depend on your accuracy (…). Captain Howard and the marines will sweep their weather deck with swivel gun and musket fire from the tops. They’ll try and even the odds for us before we board. (…) So it’s every hand to his rope or gun, quick’s the word and sharp’s the action.«

Cut to a different scene: Same epoch, same situation, but a few more ships: A collection of vessels from all over the world are facing a united enemy armada. On the Black Pearl, the captain is preparing the crew for sea battle, as above, calling out at them from atop the railing:

»Then what shall we die for? You will listen to me! LISTEN! The other ships will still be looking to us, to the Black Pearl, to lead, and what will they see? Frightened bilgerats aboard a derelict ship? No, no they will see free men and freedom! And what the enemy will see, they will see the flash of our cannons, and they will hear the ringing of our swords, and they will know what we can do! By the sweat of our brow and the strength of our backs and the courage in our hearts! Gentlemen, hoist the colours!«

One of the crew responds with the call »Hoist the colours!«, then two, then all on board. The call spreads to the other ships – Chinese, Indian, French, African – and the colours are hoisted on the masts …

In the first scene, it is the Union Jack flying from the mast. The colours hoisted in the second scene show the Jolly Roger. Both examples are fictional, not historical. They are from blockbuster films: The first captain is Jack Aubrey from the film Master and Commander. The second is Elisabeth, a courageous woman who leads the Pirates of the Caribbean in the film’s showdown. Although these speeches were never actually given in that form in real life, they are paradigmatic for two juxtaposing philosophies of leadership and organisational models: Navy Command vs. Pirate Leadership.

The navy captain has already decided for himself how the battle ahead will be won. He is a brilliant commander and has designed an intelligent plan down to the last detail. His crew is divided into functions and is highly specialised. They are given precise orders, in jargon, telling them who will have to do what and when. The captain can trust that his order will not be questioned by anyone and that everyone will enact his plan to the best of their abilities. He is the boss: the most competent problem solver, the lone decision-maker, the clear giver of orders …

What does Elisabeth do, on the other hand? She merely appeals to her men’s freedom and demands that they all give their full commitment. She leaves the decisions of how the battle will be won to each individual member of the crew. She trusts that each of them will do exactly what they consider the right thing to do in the challenging battle ahead: that collective swarm intelligence will be superior to the enemy’s military command. Elisabeth’s efficacy as a Pirate Leader is not established until the first followers attest their commitment by giving their agreement. Then, their call spreads like wildfire and catches in the other units …

It is easy to draw an accepted parallel between the military and business. Too many words that are used in the economy recall the model function of the military (consider the origins of words like chief officer, strategy, tactic, etc.). It could be more difficult to position the historical pirates as a model for successful leadership. They are usually perceived as an uncontrolled and uncontrollable horde brought together from far and wide by coincidence, who contravene all rules and break the laws to terrorize the seas and caper trade ships with cruelty and no holds barred.

I am not about to legitimize and qualify the illegality of piracy. I do, however, believe that even centuries ago, the pirates created a historical model for successful self-organization with the leadership philosophy outlined above. The economist Peter Leeson has addressed the economic and social organisation among pirates in detail. In the Journal of Political Economy, he concludes that pirates developed »one of the most sophisticated and successful criminal organisations of history«.

Pirates were not at all a chaotic mob, after all. They did have a functioning organization. It rested on a few fundamental rules and a very large degree of self-organization. Thomas Häusler says that the »enemies of humanity«, as they were called by the official authorities, were in fact »true friends of democracy«. That is probably one of the reasons they were pursued without mercy in the absolutist age. The pirate crews elected their captain – for a period of time. It was possible to replace leaders at any time, for example if they proved to be too autocratic or cowardly. The captain only enjoyed absolute authority during attacks. The only other leadership position next to the captain was that of the quartermaster; no other hierarchies were in place.

A few basic prohibitions ensured order: hard punishments were doled out for violence against crew members, theft within the crew, cowardice in battle and gambling for money. The pirates’ codes, which every member had to swear on, often guaranteed that prisoners would be treated well and women respected. They regulated the distribution of the bounty and guaranteed social securities: The pirates had a balanced wage scale, with the captain getting no more than double and the quartermaster no more than one and a half times the share of the bounty as any other member of the crew. Compare that with modern-day CEO wages, which might be as much as 300 times that of the employees! Whoever was injured or even rendered invalid in battle was given a generous compensation and therefore good security. At the same time when the crews on trade ships were given short shrift, subjected to hard drills and maltreatment, the pirates therefore established a »democratic counter-model to the autocratic trade marines« (according to Häusler). It is not for nothing that so many marines defected to the pirates, even at the risk of being pursued by the state as outlaws.

I repeat: I am not calling for lawlessness and breach of compliance in organizations! But I do want to encourage to learn from the historical facts of the pirate era. As I see it – to put it bluntly – too many organizations and departments are nowadays still being managed like marine ships and are casting away a great amount of potential that could by salvaged with Pirate Leadership: especially so in the uncertain navigable waters of the VUCA world.

By now, the first organizations are courageous enough to give Pirate Leadership a try, with democratising structures, consistent self-organization and support for freedom of decision-making on all levels. Brian M. Carney and Isaac Getz published their book Freedom, Inc. in 2009, coining the apt and provocative term of liberated companies. Frederic Laloux offered a very impressive documentation of the potential that can be realized in self-organization in the 360 inspiring pages of his recent, pioneering book Reinventing Organizations (2014). This former McKinsey associate partner provides a detailed analysis of twelve organizations from a range of fields, countries and contexts (with as many as 40.000 employees!) and documents how the abolition of excessive hierarchy and a switch to self-organization can achieve stunning effects.

For example: The Dutch healthcare organization Buurtzorg was able to reduce the care effort per client by 40% (!) by switching to self-organized nursing teams. Ernst & Young estimate a savings potential of approximately two billion Euro if this model was adopted throughout Holland.

It has been argued that this is not possible beyond the NGO sector. The French automotive supplier FAVI has refuted that point: while all of their rivals have by now moved their production to China due to the lower wage costs, FAVI is the only manufacturer of shift forks to remain in Europe, with a market share of 50 percent. The product quality delivered by FAVI is described as »legendary«, their punctuality of delivery is considered »mythical« (not a single order has been delivered late in the last 25 years). FAVI attains high profit margins every year amid aggressive competition from Chinese rival suppliers, pays wages that are clearly above the average and does not suffer employee turnover. Laloux argues that this and other achievements are due to the radical realization of self-management in the organization. Down to the assembly line, the FAVI employees direct, manage and organize themselves in small teams (known as mini-factories), without a declared manager.

A film has recently been doing the rounds on the net: Augenhöhe (a version with English subtitles is available on the site.). It presents more organizations that value self-determination and real participation – successfully so. In February and March, the TV channel arte gave several showings of the wonderful documentation Mein wunderbarer Arbeitsplatz (unfortunately only available in French and German). Like the pirate leader Elisabeth above, the leaders of organisations in this film appeal to the »free men (… and women) and freedom« in the organization.

The organizations in the films and books above that are managed in the spirit of Pirate Leadership show that the focus on self-organization and freedom of decision pay off. Beyond that, most of the people featured in the portraits confirm that they never want to work differently again. This must be another key to the potential that Rüdiger Müngersdorff addressed in his last blog contribution. If, as surveys say, only twenty percent of employees are really motivated, how great is the room for development in an organization in order to win the remaining eighty percent?

With a bit more pathos, we might say that whoever has tasted the freedom of a pirate’s life will not want to return to a marine ship. That notion will strike fear into the bones of many managers. Yet I am convinced that this is in fact the very opportunity for organizations. The quote ascribed to the much-adored and highly successful Steve Jobs is no coincidence: »It’s more fun to be a pirate than to join the navy!«

Johannes Ries

24. June 2015

Criteria for a Successful Transformation (Part 1)

Criteria for a Successful Transformation (Part 1)

Everyone knows that an organization’s viability for the future is decided by its ability to react and adapt to fast and fundamental changes to its conditions.

Many know how organizations can be modernized, transformed or »reinvented«; many know how to develop a vision full of meaning and significance, how to initiate personal responsibility and establish a culture shaped by trust – the basis for creativity, innovation, speed and agility.

Few recognize their organization as potential, a living organism with a proper soul and intention to unfold its mission in the world.

Finally, some businesses have really created organizations for a modern age that is viable for the future, that meet the requirements of the people and our shared environment on the earth.

The businesses of a modern age viable for the future are said to have attributes like an integral use for all stakeholders, a significant and emotionally binding object of the venture, sustainability, creativity, innovation, personal responsibility, teams that know how to lead themselves, a comprehensive approach, modern spatial concepts and flexible use of time, networked working and direct communication terrifically supported and shaped by digital technology, lean, speed and agility – in different degrees and combinations.

Different groups of companies are dominantly named in current discussions on New Leadership – New Organizations. One the one hand, the cult enterprises keep cropping up, including Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, which are all at the very top of the list of most admired companies (Hay Group/Fortune). On the other hand, we keep hearing from the sustainably successful classics, such as Gore, Semco, Morning Star, dm – drogeriemarkt, and the »Teal Organizations«, that have been celebrated in recent literature, e.g., FAVI and Buurtzorg. Finally, we come across initiatives like the team WIKISPEED – a car manufacture that started as a single project with volunteers only and has the potential to revolutionize the entire automobile industry.

Creative and initiative personalities create new organizations around a technological paradigm shift

A company like Facebook, which has only been active since 2004, develops its culture without being tied into a long company history. It develops this culture together with similarly minded digital natives in order to fulfill its mission to give people the potential to communicate, to make the world more open and to connect.

Personalities like Steve Jobs, Larry Page, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg for the American cult ventures and Wilbert Lee »Bill« and Genevieve Gore, Ricardo Semler, Chris J. Rufer, Götz W. Werner for the classics, as well as Jean Francois Zobrist, Jos de Blok and Joe Justice are integral to the individuality and mission of their organizations, their companies.

It is clear that founders give a company its soul. For example, the attitudes and convictions of Bill and Genevieve Gore still shape the culture of their company. They established their business in 1958 and initially operated from the basement of their private house. By now, there are 10,000 associates worldwide in a flat organizational structure without an instructive hierarchy who work with technological innovation and success in multi-disciplinary teams. They do so in manageable business units in order to ensure direct communication. »No ranks, not titles« is alive, even though today’s actual business cards do bear titles, like »Global Leader« for a given division and others. The sustainable success of the company is greatly supported by the strong reduction in hierarchical culture and one-on-one communication at eye level by Gore. These same factors can, however, also limit the company, for example when Gore expands into other countries, such as China, where a stronger hierarchical orientation is culturally ingrained.

Joe Justice emerged in 2008 as the founder of a new generation, when he established his Team WIKISPEED as an organization that grew out of a blog about a technologically exciting challenge. One of this organization’s founding elements is utterly voluntary participation.

In 2008, he participated in the »Progressive Automotive XPrice« competition and gained shared tenth place in this global competition against the giants of the automobile industry. Prize money of 10 million US Dollars was awarded in this initiative supported by the US Department of Energy. Competitors had to meet the challenge of building a car that was able to travel for 100 miles (160.9 kilometers) in real traffic conditions on one gallon (approx. 3.8 l) of fuel.

He began alone and reported his progress and obstacles in a blog. This way, he found 44 volunteers in four countries, who worked together to create a prototype for the competition within three months. Team WIKISPEED achieved a »sensational« development cycle of seven days, where the traditional automobile industry takes years. Joe named three enablers for this incredible speed: Agile, Lean and Scrum.

Development takes place in modules in separate teams. Every task is completed in pairs, so that knowledge is shared on the spot and time-consuming training can be avoided. All programs and tools that are used, which did not even exist ten years ago, are »open source«.

Use of material is kept to a minimum and waste is avoided. Visualizations of the processes immediately reveal inefficiencies and allow for their removal. The use of the project framework Scrum, which has proved itself in software development, made it possible to be stunningly fast in the development of an automobile prototype.

Team WIKISPEED now has 1000 members in twenty countries, building and selling cars. All participants provide their work and knowledge free of charge; any attained profit is distributed among the community.

With his passion and the belief that it is possible to achieve decidedly more environmentally viable mobility, Joe Justice found similarly minded people. The realization of a cooperation that relies on »sharing«, the digital options applied to permanently connect the scattered teams and ensure exchange as well as the transmission of methods and tools from software development to traditional heavy industry are elements of this rapid success. However, a public call for support suggests that Team WIKISPEED has reached its limits and that the community will have to provide new impulses in order to continue its success story. Environmental awareness, passion, volunteering, knowledge sharing: these are the striking features of a new generation of founders. The consistent application of freely available tools and agile working with lean concepts and the SCRUM project framework are the striking elements of equivalent modern organizations. Joe Justice is striving for his model to also be put to use in finding solutions for great issues of society such as tackling epidemic disease.

How, though, can traditional, hierarchical companies be modernized: companies which were not placed into a New Era by their founder and entrepreneur, but which have a long history and were established at a different time into completely different conditions?

FAVI is a successful subcontractor and automotive supplier. The company was established in 1957. In 1980, Jean-Francois Zobrist attained the post of »directeur général«; he would remain in this responsible position for 29 years. FAVI was successfully transformed to provide toom for personal responsibility, ownership and a comprehensive concept as described by Frederic Laloux in his inspiring book: Reeinventing Organizations, A Guide to creating Organizations inspired by the next stage of human consciousness (Brüssel 2014).

Zobrist faced a company with five hierarchical levels and many processes and functions, mechanisms that were exclusively concerned with employee control. Zobrist spent some months attempting to prepare his leadership team for changes, experiencing vehement resistance.

For nine months after he had taken over the management, he visited the production line every day, spoke to every one, asked many questions, but was also glad to answer all questions put to him; he tried to take his managers with him on his journey of modernization, but did not succeed. Then, he addressed his entire work force. He shared his conviction that the way in which the people in the factory were managed and controlled is unworthy and his belief that they deserved a different treatment, that they deserved trust. He announced concrete changes, including the removal of clocking, adaptations of the salary system to fixed salaries, opening the store and trusting that every one will take what they need for their task as well as the abolition of a separate canteen for managers.

He acknowledged that he himself did not know the exact shape that operative work should take in the future and invited every member of his audience to take part: »I suggest that together we learn by doing, with good intentions, common sense, and in good faith.« (Zobrist, La belle histoire de FAVI, p.38, cited in Laloux Frederic, Reeinventing organizations, p.273)

The managers opposed these changes vehemently. Zobrist made it perfectly clear that he was not going to go back on any of his decisions, but confronted them with the next step of transformation: the introduction of self-leading teams. As this meant that there would be no more management positions, he gave »security in insecurity« to his managers: Nobody will be let go! There will be no salary cuts!

Everyone was challenged to take a look around and find or create a meaningful role. Once he had abolished management roles and introduced personal responsibility, Zobrist gave no further orders, but invited the employees to develop sensible solutions, an expedient structure without hierarchy and practicable methods of operation.

Zobrist had gained a lot of trust as a person during the first months and all the measures he introduced reflected this value in the entire organization. In this case, a credible, initiative personality successfully transformed an existing organization and gave a new soul to a company. Yet, we do have to acknowledge the fact that FAVI is a company with 400 employees in one single location.

The examples above sketch out three initial criteria for successful transformations and radical renewals of a company.

- Success is significantly linked to the personality, intentions and values of the entrepreneur and/or the CEOs, as well as of course to how they translate this into their concrete Change Leadership.

- The second key to a successful transformation are clear, consistent and »lastingly« reliable structures of power and decision-making.

- The third factor of success is the decision to actively mobilize a management coalition that is not conceived in terms of hierarchy for the change. This would be a management coalition that does not target the »upper« managers, but people on all levels and from all areas. These are people who recognize the need for change, who understand the soul of their company and can bring others to resonate with this.

It is intriguing to see whether traditional large-scale enterprises are able to fulfill these conditions.

There remains one prevailing question: How will it be possible to pick up on and realize these keys to success for a radical modernization in such a way that they can even be applied to traditional and hierarchical companies with complex structures, power functions that are divided and subject to temporal limits, and a long history?

Jörg Müngersdorff

10. April 2015

Follow-ups

The leadership situation of today and tomorrow is characterized by planning ambiguities, the demand for faster adaptation and abrupt strategy alterations. VUCA is the term that was coined to describe this situation. Is your organization prepared for it?

Since last year, we have been experimenting with diagnostic tools that will be able to find your position and to provide an answer on how well organizations are really prepared for this situation. A report from inside the development of the tools for a guided future check for organizations.

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

A diagnostics instrument on the issue of VUCA

Is it really true you are in a state of VUCA in your organization? Is the situation of your business really that volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous? How do the employees and managers in your organization see it? Does the context make a difference – the organisation as a whole, a given team, a given individual? Which aspects are considered to be the most challenging? Where have successful coping strategies emerged already?

We have captured the VUCA phenomenon in several blog entries and demonstrated a range strategies to address the situation. Before an organisation or one of its units takes a measure in order to better handle its existence in a world assumed to be in a state of VUCA, it is advisable to find answers to the questions above. It is only once those answers are before us that can we start to think about possible consequences and interventions.

In this context, it is particularly useful to engage in a guided reflection on the status of your own organization. We have therefore taken a step in that direction by designing a questionnaire in preparation for our last SophiaWorkshop. This tool enables us to find out how the people in an organization really experience their situation. It is not concerned with the measurement and evaluation of objective VUCA indicators but rather with capturing subjective and individual perceptions.

VUCA is often employed to describe the outside world or the organizational context of a business: increasing volatility on the markets makes planning more difficult, for example, as it emerges that the required assumptions and predictions do not fully apply. Many such external factors exist. However, internal factors – »home-made« ones – also play an important role. Certain structures, processes, cultural patterns and ways of behaviour can result in, or at least increase the likelihood of, a situation where employees and managers perceive their environment to be lacking the necessary stability, certainty, simplicity and clarity. That can result in a number of dysfunctional behaviours and limit the organization’s ability to react to the above-mentioned uncertainties in the outside world. The questionnaire focuses on these aspects.

We are working together with the University of Manchester and Carolin Hauner in the framework of her Master’s thesis in order to develop the VUCA diagnosis tool and to continue to sharpen the focus of the questionnaire. We will also work together with industry partners in order to make sure that the result will be a useful tool. If you are interested in taking part in this process of co-creation, please be in touch to address details and the means of cooperation!

If you would like to use the VUCA questionnaire for your own organization in order to gain an initial insight into how the VUCA situation is perceived in your organization, please contact us at diagnostics@synnecta.com.

Thomas Meilinger

SYNNECTA Diagnostics

The performance triangle, developed over years by Lukas Michel and his worldwide Agility Insights-Netzwerk, is such a scientifically based model that creates a bridge between the skills of people and the challenges of organisations.

The performance triangle, developed over years by Lukas Michel and his worldwide Agility Insights-Netzwerk, is such a scientifically based model that creates a bridge between the skills of people and the challenges of organisations.

It is the early 1800s. The British warship HMS Surprise is about to engage the enemy. The crew are all preparing below deck. The portholeopens and the captain climbs down in order to commit his men to the sea battle with the French privateer Acheron:

It is the early 1800s. The British warship HMS Surprise is about to engage the enemy. The crew are all preparing below deck. The portholeopens and the captain climbs down in order to commit his men to the sea battle with the French privateer Acheron: Criteria for a Successful Transformation (Part 1)

Criteria for a Successful Transformation (Part 1)