27. June 2023

We have already written about hope as a leadership attitude* at a time when it still seemed to many to be something esoteric. Starting from Paul’s so influential phrase in the first letter to the Corinthians

»Now abideth faith, hope, love, these three; but love is the greatest of these« **

we have described hope as the capacity to hold on to the possibility of realizing something even when much, indeed seemingly everything, speaks against it. Hope speaks of the future not as a form of wishful thinking, but as the power to believe in the becoming of good even when the present makes the future seem rather dark.

In our time, when a mood of depression, of despondency, is spreading and the view into the future seems to be possible only through the haze of failure and despair, the attitude of hope and thus of trust in the possibility of success becomes extremely important. In such an apocalyptic situation, leadership means anticipating a successful future with hope and working for its realization in a targeted and confident manner.

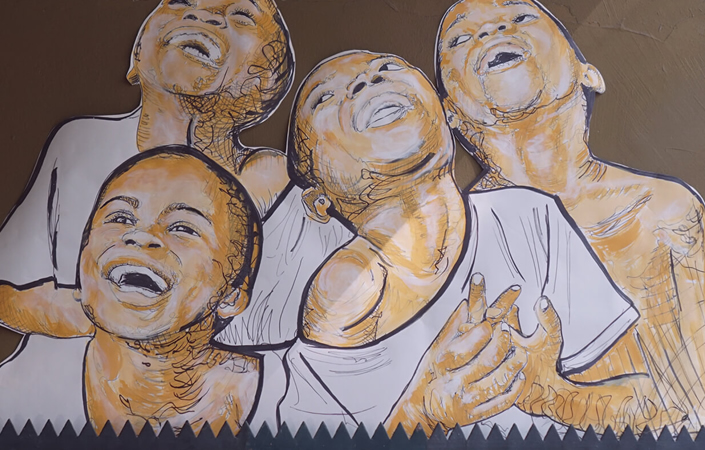

Looking at leadership attitudes, this leads us to an underestimated leadership characteristic: the preservation of a childlike naiveté. This does not mean a groundless, often narcissistic (childish) optimism that does not want to face reality, but the attitude of holding on to the possibility of »better« and drawing from hope the strength to act on reality in a way that increases the chances of making it possible. Just as grace, grace in appearance and speech is an often underestimated leadership virtue, so is naivety. It enables us to transform a »not yet« into a »now there«.

Maintaining this naiveté in the face of the many inevitable disappointments and failures in a career is no small feat, and the psychological term of frustration tolerance is a very limited description of maintaining this hopeful naiveté. Hope takes us closer to what is able to give meaning to a life as an individual and as a community. In this sense, hope carries us through the present and lets us act and shape.

Hope is not wishful thinking. It is the ability to think about the future embedded in the confidence that action is possible.

In the usual leadership trainings, one will rarely find a preoccupation with these attitudes that reach deep into the personality – they are too focused on quick tricks and tips for that. However, if we understand the need to transform hopelessness into hope, so that there is at least a chance of »better«, then it would be time to approach the topic of the future with a hopeful attitude.

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

* SYNNECTA Sophia 2017: Glaube, Liebe Hoffnung – Im Schatten der Organisation (Rüdiger Müngersdorff)

** King James Bible: And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.

Luther Bible 1912: But now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.

4. February 2022

There is a lot of talk about empathy as a leadership trait. Empathy is thus primarily located in the process of communication between people. However, empathy has another, essential dimension, which also places it at the center of strategy development.

We are now increasingly and acceleratingly confronted with non-linear dynamics – be it in the markets, in the global political situation, in the needs of the customer groups relevant to us, in social developments, to name but a few. Our cognitive analytical tools for describing this reality and its future (even near future) developments are no longer sufficient for predicting and guiding in these dynamic non-linear systems prone to disruptive events. The high degree of interconnectedness with its upsurging, circling dynamics within our communication streams sets limits to dominantly rationally oriented strategy work.

As a necessary supplement, the ability to empathize is required not only of single individuals, but of social systems, be it companies, administrations, NGO’s, religious organizations, generally of all social systems. Empathy is here the ability to feel resonance patterns of our direct and indirect environment, in short we need the empathy ability of a collective. In addition to open internal communication and reducing value judgments, the empathic resonance capacity towards a dynamic environment can only succeed if the collective is diverse – encompassing all criteria of the diversity perspective, if possible.

Synnecta’s work with groups has always aimed at the development of collective empathic capacity and has been further strengthened in recent years around the open experience of always given diversity. However, the still large homogeneity of leadership groups sets a limit to the ability to resonate with non-linear dynamics and thus also narrows the strategy work.

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

27. January 2022

Black and white.

Good and evil.

Anima and animus.

Emotional and rational.

Social and personal.

Is life made of dualities? Strategy and culture are one of these dualities we often encounter business-wise. Are we talking about opposing forces? Dichotomies seem to give us two opposing aspects on different poles, and the choice we have to make is either one or the other. Will we choose to act for good or evil? Will we focus on creating a stable business strategy or distinctive company culture? The thing is, we are much more complex.

There are so many shades between black and white, and we are living proof of the spectrum between those polarities. We are a combination of various qualities, each present by a different degree. Some traits or behaviours may dominate our nature, while others will resurface only on special occasions. We are the best representation of the polarity concept.

There is a scope and extent of each aspect contained within the other. A continuum of polarities exists within us, and we often personify a varying combination of them. Nothing flourishes in extremes, so often, the key is in finding balance. To conclude whether this is the case with company strategy and culture, we need to define the two first.

What is strategy and can you run a business without one?

Before we dive into defining what the term business strategy encompasses, we should take a step back and examine what strategy actually means. The term was introduced 15 centuries ago, originating from the Greek στρατηγία stratēgia, meaning »art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship«. Military tactics, siegecraft, logistics were just several skill subsets that the »art of the general« embodied. The term strategy evolved through the ages and came to denote a high-level plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under uncertain conditions.

Strategy is not solely reserved for the military quests anymore. Nowadays, it stands tall in all life areas, be it personal development goals, professional life goals or business goals. Our personal strategies are often shaped by our beliefs, values, and personal management system. We hardly go on living our lives, hoping everything will turn out for the better. Even if we don’t have a specific strategy pinned on our vision board, we have at least some sort of a strategy in our minds. What we’ve learned through primary and secondary socialisation and social norms stimulate our goals. Strategizing can sound scary, but we should never forget that the new experiences can serve as an excellent basis for regularly updating our life strategy by having our end goals and vision in mind.

Now, let’s try to grasp what strategy means businesswise. Researchers and practitioners agree that there is no consensus on the subject. Peter Drucker (1954), was the pioneer in addressing the strategy issue. He was under the notion that an organisation’s strategy consists of the answer to two fundamental questions: What is our business, and what should it be? Reflecting on the term’s origin, Drucker didn’t believe that »business is war« or that the business strategy should be associated with an act of warfare. Instead, he thought that strategy should enable an organisation to achieve the desired results in an unpredictable environment. Analysing the company and its marketplace to identify »certainties« was the first strategy development step.

The business strategy should serve as a framework for making both short-term and long-term business decisions. Hundreds of decisions are made in each company daily. From what software should we invest in and use, to marketing, recruiting and sales approaches, and even how each employee should make the most out of their workday. Not having a strategy in place that will guide these decisions, the organisation can be torn in different directions, less effective and profitable, and risks suffering internal confusion and conflict.

To summarise, we can consider business strategy as a set of guiding principles that construct a desired behavioural pattern. It should direct our people to the paths they should and shouldn’t take. Always having the end goal and desired results in mind is what makes both business and life strategies similar. They even point at the same impediments, the worse our starting point is and the more ambitious our goals are, the more effort it will take us to realise said strategy. We should put double the effort in to make it distinguished, and we’ll have to play smarter and work harder to make it a reality.

What is culture?

The term culture might even be more complex and broad than strategy. The consensus case is the same. There is no universal understanding and little consensus within, and even less across disciplines.

Almost seven centuries ago, when the word »culture« first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary, based on the Latin culture, it denoted »cultivation« or »tending the soil«. A couple of centuries later, the term was associated with the phrase »high culture«, implying the cultivation or refinement of mind, taste, and manners. Nowadays, it is defined as the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts. Simply put, culture is how we are doing things over here.

Consequently, organisational culture is the assortment of values, expectations, and practices that guide and inform the team members’ actions. It can be seen as the ultimate collection of traits that make our companies authentic. The term »organisation culture« refers to the values and beliefs of an organisation. The company culture also determines the way people interact with each other and behave with others outside the company.

Edgar Schein is one of the most prolific psychologists famous for his model of organisational culture. According to him, organisations do not adopt a culture in a single day. They tend to form it as the employees undergo various changes, adapt to the external environment and solve problems. Schein is famous for characterising three levels of organisational culture: artefacts, values, and basic assumptions.

- Artefacts are the organisational characteristics that individuals can easily view, hear, and feel. A visitor or an ›outsider‹ should also be able to notice them. The architecture and interior design, the office location, the employees’ manner of dressing, and even souvenirs and trophies represent physical artefacts. The language and technology used and the stories and myths circulating among the people are also part of this level. It also includes visible traditions that display ›our way of doing things‹ expressed at ceremonies and rituals, social and leadership practices, and work-related traditions.

- Values, according to Schein, are at higher levels of consciousness, and they represent the employees’ shared opinion on ›how things should be‹. The members don’t necessarily act according to these values, but they can help them classify their situations and actions as desirable or undesirable.

- Basic assumptions are the third level that makes the company culture’s core. These kinds of beliefs are never challenged since they are taken as facts. A pattern of basic assumptions evolves among the social group members. Understanding the basic assumptions gives meaning and coherence to the seemingly disconnected and confusing artefacts and values.

Schein noted that the company culture appears and solidifies through positive problem-solving processes and anxiety avoidance. The way the company solves and reacts to problems is a more prominent factor early in its history, as it will commonly face many challenges. How it responds to those earlier challenges will significantly impact the future cultural DNA. Still, every new problem has the potential to be a pivotal opportunity since new issues are not always the same as the old ones. While broader strategies and mindsets may solidify, the culture adapted by problem-solving can evolve.

On the other hand, anxiety avoidance comprises learned reactions that allow groups to minimise anxiety. Seeking order and consistency and figuring ways to minimise internal and external conflict are elements connected to anxiety avoidance. The resulting behaviours are quite stable since we tend to indefinitely repeat the responses that we know will successfully avoid anxiety.

The collision between culture and strategy

Can strategy and culture operate independently in an organisation? Should they be considered separate entities? This capitalist era enforced a result-driven approach to many companies, and many managers seem to use their strategy to justify chasing numbers, KPIs and ROI. Even though some companies might win the numbers race and double their profits, their people might be impaired in the long run. These demanding managers believe that strategy deals with the »real business« and is the route to success. They deem culture only as »panem et circenses«, using this concept just like the emperors of old used sustenance and entertainment to subdue public discontent. Like a nice thing to have that will hopefully make people happier in the foreseeable future. This complete focus on revenue can create burnt-out and overworked employees, and the culture deficit can lead to high levels of friction and productivity decrease.

Some leaders found it tempting to focus on developing strategy more than culture in the past few years of unprecedented change. Most would argue that a strategy that describes a general long-term vision without defining what it requires of the organisation’s culture is bound to fail.

An insightful Harvard Business Review article concludes that culture is always the winner when strategy and culture collide. Even the famous Peter Drucker quote says that »culture eats strategy for breakfast«. Drucker pointed out the significance of the people factor, implying that regardless of how effective your strategy may be, your company’s culture always determines its success. Even if you have the most detailed and solid strategy in place, chances are, your projects will fail if the people executing said strategy don’t nurture the appropriate culture.

Culture doesn’t refer only to bean-bag chairs at the office game room. It indicates how people act in critical situations, respond to various challenges and manage pressure, treat partners, customers, and each other. If they don’t share the leader’s passion for the company’s vision, the strategy won’t stand a chance since they won’t be keen on implementing the plan in the first place. The company will most likely struggle to execute even the trivial daily strategies, and accomplishing a new one would be out of the question.

As we all know, change is not easy, and people are prone to resistance, especially when it comes to things they are used to and hold dear. Some leaders might battle cultural intransigence for years. Connecting their desired culture with their strategy and business goals might give the profound answer to the question: Why do we want to change our culture?

Culture and strategy need to work in synergy

We need to spend a significant effort and time planning and strategizing, but company culture happens whether we work on developing one or not. There are cases it’s created unintentionally by the founders and executives. It’s worth noting that their actions speak louder than words in the process of culture creation. As time goes by, cultures tend to evolve even though modifying them on purpose can be a pretty complex process. These unplanned developments are not always for the better, and even though it might sound counterintuitive, leaders shouldn’t fight them but work with and within them.

Culture doesn’t have to trump strategy. They should work together in harmony, complementing each other’s success. Alignment is clearly essential, but it’s getting even more challenging over the past few years as priorities and strategies change in the blink of an eye. To help our people understand the ever-changing strategy, we should recognise them and show appreciation for their successes tied to our company’s values, purpose or objectives. We can ensure our team stays aligned with our business needs in their daily tasks by encouraging them to frequently and instantaneously praise their colleagues for delivering on said expectations.

Developing an in-depth understanding of what people need from each other to perform well is vital in driving complementarity between strategy and culture. We should always make an effort to learn how the culture really works while creating the strategy. Try to grasp what people talk about, criticise, prefer, remember, and admire in the company, and ponder their stories, tonality, and language. By listening and empathising, we will find the unwritten norms and values that characterise the culture and the most prominent strategy enablers (communication, technology, tools, incentives, compensation, and benefits) behind the seemingly concealed sentiments. Take the opportunity to analyse how the cultural weaknesses, like particular mindsets, assumptions, and practices, for instance, reflect on goals and productivity. You’ll probably find they limit the exploration of new prospects and potentials, preventing superior performance and higher growth levels.

To achieve the desired synergy, we need to focus on appreciating and incorporating people’s perspectives, mindsets, and skillsets. The most successful companies managed to develop a culture that has grown greater and more powerful than any individual. People are often inspired to conform to a strong culture since it’s the thing that links everyone together, no matter the department they’re in. When people become engaged with the company, the business strategy is more likely to be perceived as a personal one.

When culture and strategy are created simultaneously, they are more prone to be aligned and in full sync to complement and stimulate each other. This harmony fosters the creation of incredible organisational transformations. When we understand our business’ authentic culture, we’re familiar with all the factors, so creating a strategic business plan is almost effortless.

When we say that culture is critical, we’re not undermining strategy and leadership. A particular strategy a company employs has better prospects of thriving if it is supported by the fitting cultural characteristics. Strategy is important, but if we’re looking for long-term success, it must be accompanied by a strong culture. While the strategy will answer all the »what«, culture should define just »how« people will put it into good practice. Prospering companies don’t think of culture as an obstacle they need to tackle but as a change accelerator, their competitive advantage. Even if companies are performance-driven, they need to be primarily person-centred and values-led.

Jörg Müngersdorff

9. November 2021

Throughout its long history, the Western world has returned time and again to the same demand: there must be a sense to your life, your existence must have a purpose that goes beyond the measure of life itself. Viktor Frankl has it that this can be something quite individual, but mostly, we are asking for something bigger, something that traverses a whole life. In national movements, for example, it has even gone as far as self-sacrifice. Children are already confronted with the need to declare a purpose in young years: »And what are you going to be one day?« Be useful! Fill your life with a task, a purpose. The message remains the same: What are you doing this for? What is the purpose? What is the sense? Life itself is not enough, it has to relate to something else, something greater.

As purpose concepts are gaining ground, they are pitching that demand right into the heart of businesses. They emphasize their claim: Pick a task, have a purpose! Choose an employer who also has a greater purpose. Be part of a community of sense. The core message is that a successful, fulfilled life must be borne by a purpose. Once you find yourself in your community of purpose, you will be motivated and engaged. That sounds good.

There is a flipside, though, which often leads to disappointment, fatigue, exhaustion, even a sense of failure. The need to have a purpose in life turns into an interior demand, an obligation. In other words: Justify yourself

The need for self-justification is one of our deepest individual and collectively shared beliefs. It calls upon a higher instance: a judge to whom we have to justify ourselves. In our individual lives, that role is often given to our parents. Casting a wider arch, it becomes increasingly unclear who will even pass that judgement.

What is it that we have to justify? First, we need to justify the sense, the purpose that we have given to our life or that has been given to us. Is my purpose a good and valuable purpose against an exterior measure? We ask that question of ourselves, but nowadays also of companies: does the business serve a good purpose, is it borne by a sense that transcends its mere task of being an economic success? This is the first step of justification. It leads to a second justification: Do I, do we fulfil our purpose? Once again, we are facing a judge and a jury. (Add to that the images of our culturally shaped background: it’s about heaven or hell.)

In my coaching work, I often encounter people who despair at this obligation and the expected judgement. They lose their joy in life and in existence against the backdrop of the judge’s ruling that they are foreseeing. When coaching addresses mindsets, it creates an awareness for these demands for a purpose. It also lets us experience which judges we effectively project in order to reinforce this life obligation.

A look at the role of CEOs reveals that the jury is cast so much more widely today. While justification used to be due only to the shareholders, it is now also owed to employees and to society. Those are quite differing scales.

The need to justify our life and our actions is surely an opposition to arbitrary selfishness. However, it can also dampen lively spontaneity, stop us from doing things for the sheer will to do so and obscure our own imagination as part of innovative action. Günther Anders posed a question that provides a fine reason to take a closer look at our own landscape of self-justification.

»Why do you suppose at all that a life might have to contain something else than just being, or even that it is possible for life to have such another thing – the very thing you call a purpose?«

(Günther Anders in Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen)

#myndleap #mindset #mindsetarbeit #mindsetcoaching #kollektivesmindset #synnecta #denksinnlich

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

This article was first published at www.myndleap.com

© Artwork: Mitra Art, Mitra Woodall

3. November 2021

Shifting the Meaning of Leadership Roles: Thinking Leadership from the Employee Perspective

1. How does the meaning come to be shifted?

The Western world has some specific cultural patterns. One of these calls out to us already from the Story of Creation in the Old Testament: »…replenish the earth, and subdue it!«, and it paints an expectation of pain and suffering. We are called upon to be doers, designers, movers. That is the core of the leadership role: design, do, create. Our modern experience of a global, networked world and its dynamics, as well as the confrontation with other cultural assumptions and values casts doubt on our notion of a confident, designing subject who has been given the world as a creative space. The modern experience appears different: it is not us who subdue the world, but the world that subdues, even overwhelms, us. Instead of scaring us off, though, this insight makes us look for new ways of finding a balance between designed influence and acceptance of the fact that the world shapes us as much as we shape it. It is an experience that also shapes our notion of leadership: the confident role taken on by a designing manager is being challenged by the potential of leadership by collectives.

We have reached a point where we are more likely to describe a manager as someone who enables, sponsors, moderates. We speak of serving managers with the values of humility and caring. It is the path from a strong ego to being part of a greater community.

It appears as if the manager of old had surrendered in the face of complexity, contingency and acceleration. That kind of leadership can no long fulfil the role of the knowledgeable designer and is facing the limits of its own confidence. Hence an answer is sought in the potentially more powerful and more intelligent collective and its multitude of voices. We trust in the wisdom of many views, different discourses and we believe that the collective as a group with a range of perspectives is more likely than the old manager-hero to succeed at the complex tasks of the modern world.

This development goes hand in hand with an insight that the Western dominant model that everything has a reason and can be based on a cause is powerful, but not universally applicable. A complex, accelerating and dynamic world teaches us to look at events in a systemic way: we view events as interactive and interwoven conditions in which we cannot find a single, unmistakeable cause, but instead find networks that might have caused the event we are seeking to explain. Knowing a single cause shows us a single goal-oriented path of action. A network of relationships forces us to follow feedback whatever we do, to become part of the network, to learn to live with the network. (Hence the altered understanding that mistakes, by triggering feedback, are an opportunity to learn.)

2. Has the old leadership role become obsolete with the turn towards the collective?

In order to master the challenges we face, to find an answer that serves the whole, we surely need the many voices of a diverse collective: we need open discourses without fear. For these discourses to be successful and the many voices not to get stuck in unforgiving positions, we also need guides, an orientation and the ties to a common horizon for whatever is needed at that point. It remains the leadership task to provide orientation, carrying the entire risk of having been wrong. Leadership must surely learn to accept that the subject is not the mighty centre but a part of the whole with a very specific role in that whole. It is always a painful task to learn that I am limited and restricted and that the path to overcoming that limitation are the others. There is another old adage that has accompanied the Western people, passed on by an Ancient Greek oracle: Remember, you are a human! Only a human, but also a human. Hannah Arendt attributed to these humans the ability to make a start. That also remains a leadership task.

3. Is the collective ready to assume leadership tasks?

In many years of working in group dynamic settings, I have seen how difficult it is to attain common orientation and goal-oriented cooperation in groups that lack leadership. In addition to the known group effects (finding roles, positions and meanings in a social field – emotionally driven effects), the development of collective, limiting patterns of perception, thinking and decision-taking form the greatest barrier to a multi-perspective and open dialogue. Together with the emotional dynamics of group cohesion, it reduces the opportunities of multiple perspectives, shrinking the group into – usually subconscious – groupthink. Without directed work on these limited patterns, groups stay far below their level and cannot achieve their given task: to better manage complexity. The dynamics of groups keep covering up the factual focus and, as psychoanalysis described for individuals, access to the collective mindset as a subconscious entity is boarded up by many defence mechanisms. This is why working with the collective mindset requires a deep expertise in group dynamics. It is the only way to manage the new balance in leadership: a more productive balance between leading and being led.

#myndleap #mindset #groupdynamic #collectivemindset #newleadership #synnecta #denksinnlich

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

This article was first published at www.myndleap.com

© Artwork: Mitra Art, Mitra Woodall