Crisis Communication III

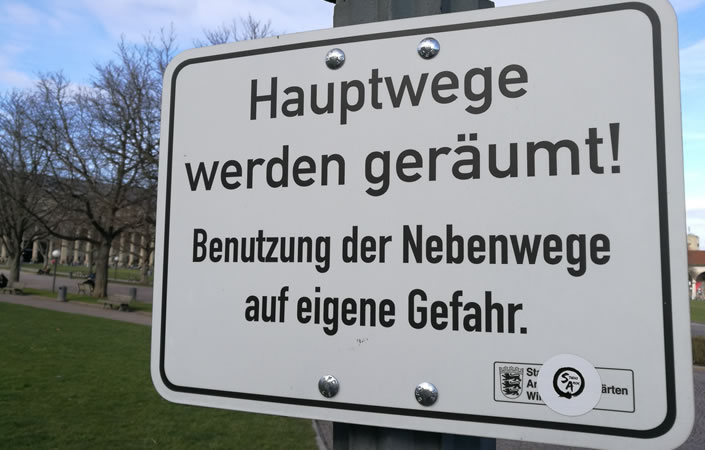

Crisis Communication III Few remarks on the announcement of the bad news It is an event that captures the attention of the managers involved. Although it is only one step in a longer process, it is the central event because it sets the tone for the whole following...

Crisis Communication II

Crisis Communication II The dilemma of local leadership or A deep conflict of loyalties There’s the decision. Costs have to be reduced, a reduction in staff is pending, perhaps the closure of a site or the sale of part of the company. The local management has the task...

Crisis Communication I

Crisis Communication I Transparency makes credible – the need for honest leadership It is a classic starting situation: A general manager, a plant manager, a divisional manager is informed that significant redundancies are imminent in his area, that a site is to be...