25. October 2019

In the last blog article we explained why the digital transformation is not just yet another change – and how you can master it. It has become clear that the digital transformation represents a fundamental change. And it demonstrated how a holistic approach can systematically analyze the effects of the transformation. The question today is: How can people be won over to transform?

Because one thing is clear: without taking the people along this path, the digital transformation will terminate in a dead end. Or in other words: those companies that manage to take their employees with them on the road to digital transformation will be more successful than those companies that fail to do so. If you want to successfully transform your company, you need to consider the seven fundamental processes that are at work in every change.

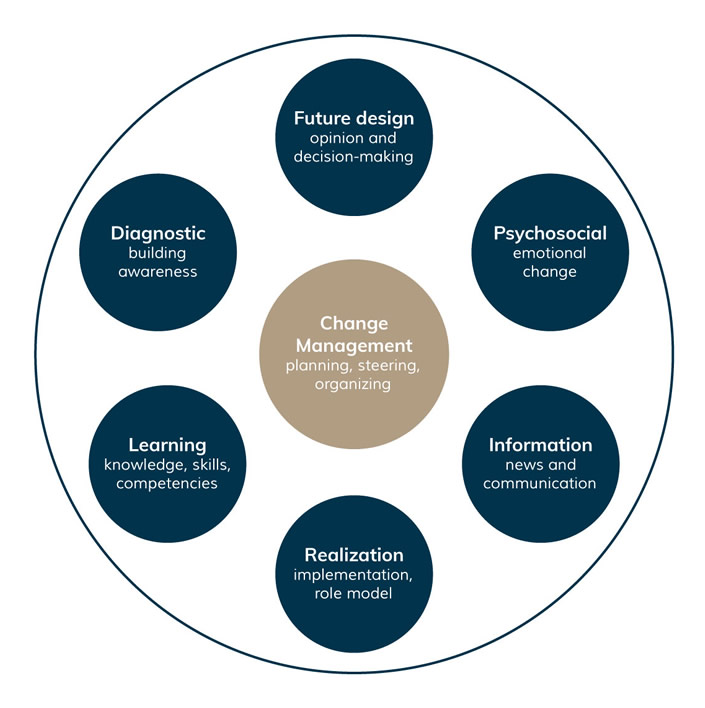

The seven fundamental processes of a transformation

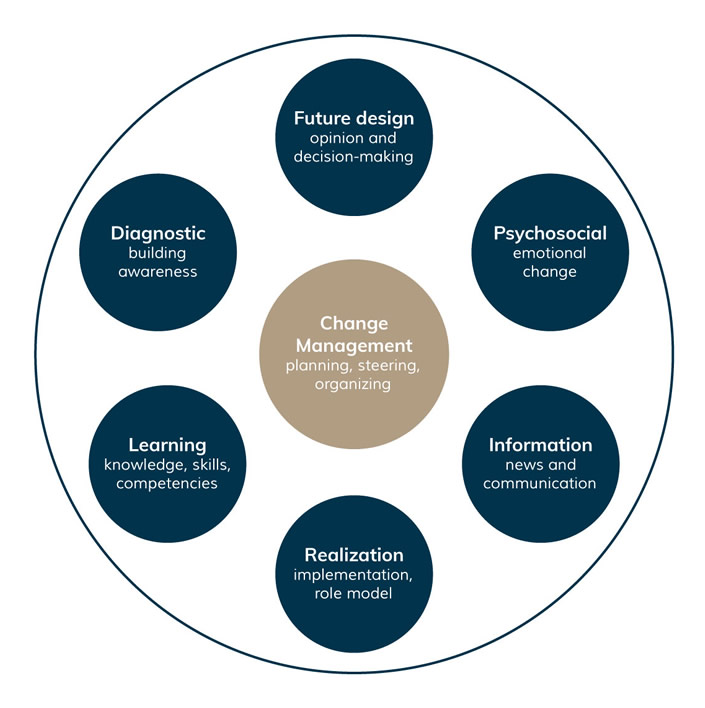

Every change project and especially every profound transformation require a complex interaction of different processes. The »system concept« according to Trigon (Professor Glasl) identifies seven fundamental processes that have to be considered and managed. The model has been in use for decades and has proven itself in practice as a useful tool for steering transformation processes. The terminology of the processes is sometimes a little difficult to get used to; however, out of respect for the authors, we orientate ourselves here on the taxonomy of Glasl, even if we would occasionally choose other terms ourselves.

Overview of the central tasks of the seven fundamental processes of a digital transformation

The following processes are effective and must be observed in every transformation or change project.

- Psychosocial processes serve to influence the emotional aspects of a transformation.

- Diagnostic processes should create awareness for the necessity of the change.

- Information and communication processes announce news and make resonance and participation possible.

- Learning processes convey the competences and attitudes required for change.

- Future design processes serve the formation of opinions and decision-making.

- Realization processes lassen die Ideen Wirklichkeit werden.

- Change Management-Prozesse turn ideas into reality.

Important: Although the processes are interlinked, they do not follow a fixed chronology. They are therefore not successive phases, but at times also parallel threads of development. However, there are »typical« procedures that often prove useful in reality. More about this aspect at the end of the article.

Psychosocial processes

Psychosocial processes are central to the success of any major change. Behind this bulky term lie the emotional aspects that go hand in hand with organizational change. These are often not at the top of the decision-makers’ agenda. However, they are the critical success factors from the point of view of organizational development.

The central task of psychosocial processes is to positively influence the emotional aspects of a transformation. In reality, change processes are always associated with uncertainty and unforeseeable events. Especially in the digital transformation, the perceived uncertainty can be huge for employees, as professional identities change.

The protection or satisfaction of basic neurobiological needs is not only the task of the leadership, but also of those responsible for a transformation.

Examples

- The »digital transformation« is leading to completely new job profiles – while old job profiles and positions are disappearing or at least becoming less important. So for the individual employee, the question automatically arises: »Will my job still exist in the future?« – »Will my commitment, my skills, my expertise still be needed and valued in the future?«

- Restructuring goes hand in hand with uncertainty about future accountability and sometimes disciplinary responsibilities: »Who will be my boss?« – »Who will be part of the team?«

- The introduction of agile working methods (Scrum, Kanban, Design Thinking etc.) or the »agile transformation« of an entire organization lead to completely new processes, which also require a changed »mindset«. Not everyone wants to face this challenge: »Will I be able to cope with these changes?« – »Do I actually have to do this to myself?«

Diagnostic processes

Not every approach or every tool work equally well in every company. What was successful in one company may be taboo or inappropriate in the next. Important: The approach must fit the corporate culture. Diagnostic surveys can be used for all phases: Depending on the change, these can be useful at the beginning, during or at the end of a transformation process.

The central task of diagnostic processes, in addition to examining the »cultural fit«, is above all to »create awareness« of the necessity of change. A simple survey can become the starting signal for a change if it shakes the decision makers awake.

Examples

- 360-degree feedback across the organization can provide illuminating insights into the leadership culture.

- An employee survey can provide a startling picture of the mood in the company and thus be the trigger for a transformation of the company – as happened at the Upstalsboom hotel chain with its owner Bodo Janssen.

- With instruments to survey the corporate culture, the characteristics of the organization can be determined.

- The effects of a transformation process can be observed through online surveys, but also through regular cross-hierarchical presence workshops with managers and employees from other disciplinary areas.

Information and communication processes

In the classical world of change management, change processes were »rolled out« from top to bottom, along the hierarchy. In countless small groups of workshops, superiors were informed first and employees only later on; mostly with ready-made PowerPoint slides about the changes. Participation was only sporadic, if at all, and hardly more than a fig leaf. This approach regularly contributed to the failure of change projects. The key to the success of a transformation, however, lies in the participation of the employees. For this reason, dialogue events or other participation formats are crucial to success. The digital transformation in particular opens up many opportunities to report on the gradual success and to share »success stories« with the team.

Strictly speaking, information processes and communication processes can be differentiated. Communication is characterized by the fact that there is not only a sender and a recipient, but a dialogue develops.

In this sense, »information« refers to a one-way street on which decisions and news are sent out – e.g. in the form of video speeches, e-mails or on the notice board. The question is highly relevant, who I inform when and about what exactly: Content, tonality, time, medium, target group. Legal issues (e.g. information of the works council) also play an important role here.

With some transformations, special sensitivity is required. Particularly when it comes to staff reductions or changes in responsibilities, direct contact with those affected should first be sought. At the same time, communication to the entire company must take place very promptly in order to keep the unavoidable »office grapevine« as low as possible.

»Communication processes«, on the other hand, are characterized by the fact that they invite to dialogue and explicitly request direct feedback. Typically, this takes place within the framework of face-to-face events, in which both the response to the presented content is queried – and the participants are invited to get involved (see below). Dialogue events of this kind thus combine aspects of »resonance and participation«. As a decision maker, I can demonstrate personal commitment at these events and show how important the topic is to me (keyword »management attention«).

Learning processes

Learning processes in the stricter sense can include training and qualification of employees. The starting point here is often the question: »What new skills and competencies do employees actually need to have to be able to act in line with the new idea for the future?« In addition, social learning can also be used to design measures to promote the exchange of ideas among employees and thus support informal learning. This makes it easier to transfer knowledge from »tacit knowledge« – i.e. knowledge that is difficult to convey in writing or graphically. In addition, social learning is often a prerequisite for changing the mindset. And an updated mindset or new, changed attitudes are the rule rather than the exception in transformations. Especially in the digital transformation it is not only the new software programs and processes that need to be learned. Rather, the understanding or mindset must develop that learning becomes a permanent development movement. In the past, people learned a new interface that was valid for the next 10 to 15 years (example: SAP). Today, there are rather countless »apps« that require flexible familiarization. What we already know from smartphones as a natural part of our lives will also spread to software in business. On the private smartphone, we learned to click and type until we understood the (preferably intuitive) user guidance. As a decision-maker, I have to support this learning process and give the employees in the company the opportunity to try it out. Learning is a cultural characteristic and is therefore closely linked to the feedback and error culture in the company.

Examples

- Learning new software and new process sequences

- Leadership and feedback techniques

- Methods and tools of self-leadership

- Reflection on one’s own mindset in relation to agile procedures

At best, learning becomes part of the corporate culture. The formats for teaching competencies (knowledge, skills and attitude) have become more diverse in recent times, as the trends of »corporate learning« show:

Future design processes

Processes for shaping visions of the future serve to form the will within the organization and support the commitment of those involved. Well designed, they thus promote sustainability and increase the chances of success of subsequent implementation.

Just a few decades ago, processes for shaping the future were the exclusive domain of corporate management. Today, it is increasingly recognized that it makes sense to involve employees at an early stage in the design of ideas for the future. This insight refers not only to the conception of new ideas, but also to the sustainable implementation in the course of change. In short:

People find ideas better which they have helped to create.

The basic neurobiological needs of autonomy and self-efficacy play a central role here. The appropriate extent and type of involvement are strongly dependent on the respective company. The task of the leadership is to make the space for participation as large as possible. Digital transformation in particular allows – or even forces – many degrees of freedom – simply because many ideas for the future are still in motion and have yet to develop. There is simply no blueprint for digital transformation. This makes the involvement of employees all the more valuable; in terms of generating ideas – and above all in terms of sustainable implementation.

Examples

- Workshops with the management to develop a vision or a mission statement for the company

- Elaboration of a meaningful change story with the Core Change Team

- Large group events (in the style of Open Space and Barcamp) in which employees can contribute their ideas.

- Support for initiatives driven by employees (see »Working Out Loud« (WOL); more on this in the article on Social Learning).

Realization processes

The sustainable realization of the envisaged future idea is the central objective of every transformation. This is where projects and tasks are realized and implemented. Managers also play an important part as role models for the new culture. Often, a more modern understanding of leadership is explicitly part of the transformation idea (cf. our series on leadership of the future).

In the past, change projects were »rolled out«; today the focus is on participation at an early stage. It is not only about the perception of the resonance (as with the described communication processes), but also about the participation in shaping the future as well as the actual implementation of ideas. The processes of shaping the future and realization are therefore closely linked and run parallel at times.

It often makes sense to tackle targeted transformations relatively quickly and in small steps; and to communicate the realization of progress effectively (cf. information processes). The digital transformation allows the possibility to present innovation in an innovative way. As a decision maker, I can design communication in such a way that content (digital transformation) and medium form a unit here – in the sense of »walk the talk«.

Examples

- Kick-off events (»Big Bang event«) give the official starting signal for the reorganization of a company or the introduction of new software.

- Regular updates on project progress via various media (intranet or ESN, mailings, events such as Open Office)

- Symbolic actions (»flip the switch«) of the management board

Change management processes

Last but not least there are the change management processes. This includes all measures that serve the planning, controlling, coordination and evaluation of the transformation. Actually, the term transformation management processes would be more appropriate, since by no means only temporary change projects are affected. This includes the establishment of a steering body and possibly a further resonance group, but also contact with the relevant decision-makers of the management so that decisions can be made quickly.

Due to the significance of this task, it is important to be strongly positioned within the company in this respect or to obtain external professional advice.

Typical approach to steering the fundamental processes

As mentioned above, the fundamental processes are not phases with a »natural« sequence, but rather interconnected and in principle independent processes without a chronological order. From the point of view of transformation management, however, some sequences appear more frequently than others in everyday organizational development and can be described as typical. Here are three examples.

Case 1: After countless employee surveys, employees are »survey tired«.

Instead of a new survey (diagnostic processes), it makes sense to remind employees of the purpose of the change (future design processes) and to respond to their emotional sensitivities (psychosocial processes). In addition, there should be rapidly visible changes in the sense of »quick-wins« or immediate measures (realization processes) in order to strengthen the confidence in the change.

Case 2: The climate between the participants is negative

and conflicts prevent constructive cooperation.

The first priority is to clarify the relationships (psychosocial processes) in order to re-establish a workable basis for cooperation. A survey (diagnostic processes) can bring clarity about previously unrecognized moods in the company, which may smolder in the organization independently of the individual case of conflict. Subsequently, attention can be drawn to the joint shaping of the future (e.g. elaboration of a corporate vision/strategy).

Case 3: Employees distrust the management’s commitment to change.

If employees have lost confidence in the leadership’s ability to implement (after unsuccessful declarations of intent), »strong« and immediate symbolic actions on the part of management can »send a signal« and thus revive confidence in the management’s will to change (»This time they seem to mean it up there!«). Future design processes and realization processes should therefore take place quickly side by side. Afterwards, management should seek closeness to the workforce in order to overcome broken-up gaps (psychosocial processes).

Of course, the cases described above are very simplified and the measures are by no means to be understood as a »recipe«. Each transformation process is individual and brings with it its own challenges – and opportunities – and requires an individual approach. In addition, it is important to keep in mind that each »process« can include a wide variety of possible measures.

From the point of view of the decision-maker, it is important to keep an eye on all processes and to have them coordinated and monitored by internal and, if necessary, external transformation partners. Depending on the transformation and individual case, the processes have different impacts. All too often transformations fail because one or more of the aspects have been ignored. If you want to transform your company, pay attention to the professional management of the seven fundamental processes.

Daniel Goetz

Photo: anh-tuan-to-U by unsplash.com

This article was first published by the author in agateno’s blog at www.agateno.com.

Are you responsible for transforming your company? Then this question will be of interest to you: How can HR drive the transformation on an equal footing with management?

In March 2020, we will start our new »Transformation Partner« training course in Cologne. Find out more on our website hr-transformation-partner.com.

6. July 2017

A process of change can take on many guises. It can be a major crisis or a great opportunity. Yet every single process of change involves two decisive components: Anxiety and Trust. There is no certainty in life. It is never there, but its absence is most apparent in processes that are first and foremost about change.

Uncertainty, however, creates anxiety. Uncertainty about what we are facing implies potential danger. Potential danger is the basic trigger of anxiety. Part of our fear of that which we do not know is anticipatory anxiety: the fear of fear itself. This anxiety is the kind of fear that paralyses us humans more than anything else. It makes us blind. Chronic anticipatory anxiety and excessive fear block a clear view of reality and thus disable the ability to perceive potential. It prevents learning, flexibility and development. These, however, are tools that are essential to surviving a crisis.

The success of a process will hinge on your attitude towards fear and anxiety (your own as well as that of your colleagues) and the way this attitude affects your relationship to confidence and hope. What courses of action are open to managers in a situation that is shaped by uncertainty? How can they reduce anxiety and establish trust; how can they make sure that they and their employees will not fall into a state of anxious paralysis in the face of potential danger and threat? If you allow room for these questions and attempt to find answers to them, you will be able to master any crisis.

Fear: Processes of change entail concrete threats for all those who are involved. These can include the loss of a workplace, status loss, an increased workload, the fear of not being good enough. Each process of change has its winners and its losers. These fears are real or are felt to be real and refer to potential realities. They are concrete and relate to a particular issue.

Anxiety: Diffuse anxieties do not need to be directed towards a given object. These are basic anxieties that are contained in the essence of human existence and are differently well developed in each person, depending on personal histories. They emerge in response to individual triggers.

Managers can respond to both fear and anxiety in positive ways. Basic anxieties include:

- the fear of change – experience of transience and uncertainty

- the fear of finality – experience of bondage

- the fear of closeness – experience of dependency

- the fear of individuation – experience of isolation, lack of shelter

Avoidance strategies in response to anxiety

- Avoidance: Avoidance of situations and persons who trigger anxiety.

- Trivialization: Belittling the anxiety, playing down its symptoms.

- Repression: Deflecting from the anxiety, the anxiety is numbed and protective excuses are made.

- Denial: The anxiety is utterly ignored. It is given no place in the individual’s range of emotions.

- Exaggeration: Overdrawn precautions and their compulsive repetition aim to reduce anxiety.

- Generalisation: Creating norms to correspond with individual anxieties.

- Heroization: Only the strong can handle anxiety. You are a hero.

In the short term, these strategies can reduce anxiety. However, they all result in an inability to deal with the threatening situation in a clear, appropriate and constructive manner. It becomes impossible to employ the available resources for a constructive treatment of the crisis. The potential to actually solve the crisis is thus blocked. In the long term, avoidance strategies result in rising personal anxiety levels. The avoidance strategies will increasingly fail, and this failure will cause social, psychological and physical symptoms of illness.

More than 26 per cent of medical complaints registered in the EU are due to psychological disorders: they make up more incidences than heart disease and cancer. The greatest part of these 26 per cent are related to anxiety and depression.

More than 26 per cent of medical complaints registered in the EU are due to psychological disorders: they make up more incidences than heart disease and cancer. The greatest part of these 26 per cent are related to anxiety and depression.

Fourteen per cent of Europe’s total population have suffered anxiety disorder!

Anxiety causes personal suffering as well as a loss of creative and productive capacity: it is, beyond anything else, an enormous macroeconomic factor. The statistics of the Bundesverband der Betriebskrankenkassen [federal association of company health insurance funds] show that a quarter of all sick-leave certificates and a twelfth of all days off work in Germany are explained by psychological disorders. Since the early 1990s, the percentage of sick-leave due to such disorders has more than doubled.

It used to be the case that an employee entering a company could be certain that one day he or she would be handed a golden watch to mark their 25 years with the company. Nowadays, it can happen that everything is fine on a Thursday and the department is closing down on the following Monday. Restructuring processes in companies can trigger anxieties when they result in demands that individuals fulfil new roles that do not match their personality: for example, when an assiduous accountant with a knack for numbers is suddenly required to enter customer service and give advice. In the modern society we live in, all relationships are qualified by the possibility of their dissolution. This considerably adds to a sense of uncertainty.

What needs to be done?

1. Recognition

- The first thing managers have to do in order to properly deal with active anxieties in a situation of change is to recognize them. It does not matter whether these are concrete fears or diffuse anxieties, whether they are realistic or not.

- You will find it easier to deal with the anxieties of others when you are able to recognize basic anxieties in your own life for yourself. Once you have accepted your own fears, you will not need to resort to a defensive reaction when you are confronted with anxiety.

2. Reduction of Anxiety

The emotional opposite of fear is trust. There are two types of trust. They are interdependent:

- Trust in yourself and your own capabilities and

- Trust in others

Fear knocked. Trust opened. There was no-one there. (Chinese)

When confronted with a situation of change that triggers their anxieties, employees in a company will turn to their superiors for guidance. As a manager, you thus have to contribute to ensuring that

- your colleagues trust you

- you create situations and an atmosphere in which your colleagues can believe in themselves and their capabilities (self-efficacy).

We know from child psychology that certain experiences cause a child to lose their absolute trust in themselves and their environment. These forms of disappointment also affect adults, thus reducing their belief in themselves and their environment, e.g., their business:

I. Trust in management is lost when:

- there is a sense of being left alone; when there is nobody there when help is needed

- superiors announce something and do not keep it

- superiors appear to be acting without reason or arbitrarily, especially with regard to negative sanctions

- superiors vent their temper on their employees

- there is no continuity in management behaviour. In other words: your colleagues will only trust you if there is a clear and functional management coalition

II. Trust in one’s own person and capabilities is lost when:

- demands that are made are continuously set too high, so that employees will repeatedly experience a failure to succeed

- criticism is delivered much more frequently than appreciation is voiced

- employees feel that they are helplessly delivered to a situation

- superiors are overly protective and controlling, they don’t allow their employees the room to make their own experiences

- they cannot experience their own ability to learn, effect and be independent

- there is no differentiation between uncertainty regarding the self and uncertainty regarding the situation

- superiors or employees feel that they have to be flawless

Trust in oneself and one’s own abilities will rise, given:

Experience of self-efficacy

Whenever people experience that they can have an effect, that they are actors who make a difference, their trust in themselves will grow. This is most effective when a person has successfully handled a difficult situation. If these successes are then ascribed to that person, the expectation of self-efficacy will grow most: difficult future situations are faced with more confidence and individual failures are met with a greater tolerance for frustration.

Substitutional experience

Watching other people master a difficult task or believe that they can handle it, raises a person’s own belief in their ability to handle it. Greater similarity and proximity between the person watching and the person being watched will increase the influence the example can have.

Verbal encouragement

People who are met with confidence and benevolence and who are trusted by others that they can master a given situation are more likely to believe in themselves than those whose abilities are doubted. At the same time, it is important not to make unrealistic demands.

Emotional control

People who are able to influence their level of agitation (e.g., using breathing techniques, disciplined thought and self-reflection, sport to vent physical excitement, etc.), are more likely to believe in themselves and their self-efficacy, as they experience that they are not helplessly delivered to their own emotions and states of agitation.

Thus, the following is valid: There are many reasons to be anxious. When anxieties are recognized and not avoided, the human ability to act will be retained and people will be able to handle crises. And to stay healthy. There is no certainty. There is confidence.

Fear and joy are magnifying glasses. (Jeremias Gotthelf)

Rüdiger Müngersdorff, Katja Schröder

3. December 2015

Cultural anthropologists have addressed the cultural aspects of organizations and companies since the 1920s, beginning with the Hawthorne Experiments. Now, economists and management have come to recognize that organizational culture is a resource for economic success that should not be underestimated. There are two trends in the debates about a precise definition of organizational culture: while one group assumes that every company has a culture (instrumental view, objectivism, organizational culture as subsystem), the other side argues that every company is a culture (institutional view, subjectivism, organizational culture as an encompassing system) (see, e.g. Franken 2004: 219f). Both groups, however, tend to disregard a fundamental aspect of culture: its dynamic nature.

In the following analysis, organizational culture will be considered as a field of discourses in tension within which employees have a range of possible courses of action at their disposal. Following Rainer Keller’s sociology of knowledge approach to discourse (Keller 2005), discourse is understood to be »ensembles of meaningful units structured by content and form, which are produced within a specific set of practices: structured connection of interpretation/action. They provide meaning […] to social phenomena and therefore constitute their social reality. They are simultaneously an expression and constitutive condition of the social.« (Keller 1999).

According to cultural anthropologist Wolfgang Kaschuba, a discourse includes

- a set system of argumentation,

- a system that defines a topical field and sets the rules of engagement,

- a thought system that configures the perception of reality and

- a social practice system that connects manners of thinking and acting. (Kaschuba 1999: 236f)

Every social system prefers a certain type of discourse and controls, organizes and channels the production of all discourses so as to maintain order (see, e.g., Foucault 1994). Philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, however, made it clear that any single social system is always percolated by several discourses, which will either support each other or are mutually exclusive in a state of the differend (Lyotard 1987). Even where one discourse is excluded or suppressed by the publicly advanced and currently more powerful discourses that does not mean that it does not have any influence or cannot even become that major discourse in particular situations.

From this point of view, every company is a lived culture, where the manner in which culture is lived will be defined by (competing) discourses. A company can, however, also have a culture, e.g., by having a displayed culture that may be enforced by top management by means of discourse in order to attain a principle set of concrete values, norms and rules. The discrepancy between displayed and lived culture is, as change projects show time and again, one of the most important reasons for resentment and a lack of motivation among the employees. In this context, a differend in discourses will soon develop into internal crises of plausibility within companies, and these will sooner or later seep outside via the employees and can cause lasting damage to the company’s, brand’s or product’s reputation.

However, change management that goes deeper than the mere surface essentially produces a differend in discourses and therefore a field of discourses in tension: the »old« lived organizational culture (condition as is) is confronted with a »new« displayed organizational culture (condition as desired). Change management has to face the challenge of turning displayed into lived culture – easily said, but much more difficultly done. Each lived organizational culture has discourse resources that can support change towards a displayed culture; it can, however, also raise discourse barriers that will hinder successful change management.

Against this background, cultural anthropology and its own theoretic, methodic and practical set of tools emerges as a leading discipline for a change management that has a sensibility for culture and therefore will have a lasting effect…

Johannes Ries

This text is an extract from the article »Führungs-Kraft Unternehmenswerte: Kultursensibles Change Management im diskursiven Spannungsfeld von Unternehmenskulturen«, published in the anthology »Die verdeckten Spielregeln der Veränderung«, ed. by Johannes Ries and Susanne Spülbeck, Lit-Verlag, 2015. Available at bookstores.

3. December 2015

Imagine you are an employee in a medium-sized business with a history. You are well connected within your organization, are considered creative or you are committed – ideally you are even all three of those things. You are still several levels from the top of the company hierarchy and at this point you are certainly not at the forefront of important, strategic projects.

Imagine you are an employee in a medium-sized business with a history. You are well connected within your organization, are considered creative or you are committed – ideally you are even all three of those things. You are still several levels from the top of the company hierarchy and at this point you are certainly not at the forefront of important, strategic projects.

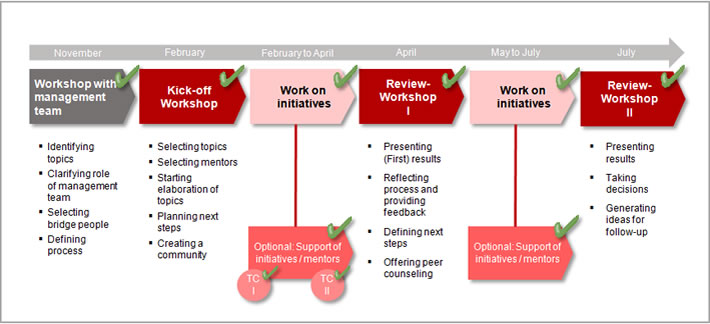

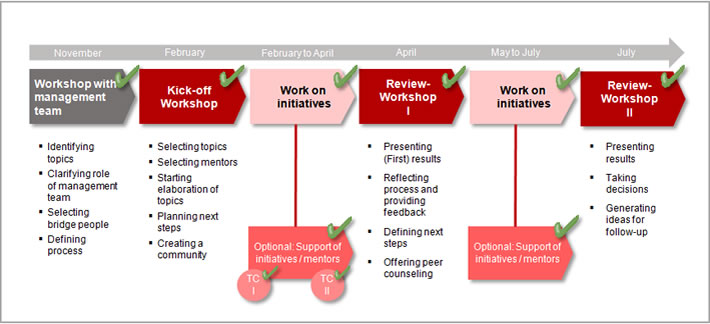

One day, you and several other colleagues receive an offer from the management team: If you want to and feel ready for it, you are invited to incite »bottom-up« changes in the company, to think important topics »out of the box« and bring them forward on your own initiative. This approach is supposed to contribute to enlivening and fostering the dynamic of the company culture in the context of a long-term strategic (re-)orientation. It is the hoped that this will be the way to new, future achievements and a continuation of a successful company history. In practice, you will be able to chose a topic during the kick-off event – depending on personal interest and inclination. This topic would then be yours to work on freely and on your own responsibility. There will be no additional payment, special time budget or any other resources made available to you in any official way. A mentor from the management team will be available to you for support, plus there will be an offer of optional coachings and supervisions.

Well? Does that sound tempting to you, somewhat strange, fairly unclear or somehow exclusive and exciting? Are you maybe asking yourself why you of all people – the person described above – were invited, and what will happen if you fail to take up the offer? On the other hand: how serious is the management team about this? Of course also: How are you supposed to handle this on top of your existing workload?

These and many other questions were posed by the bridge people who had been invited to the kick-off event. All of the almost thirty employees who had been contacted followed the invitation and only two of them left in the course of the process – for a reason and obviously without negative consequences for themselves but rather as living proof that this was perfectly possible. The entire idea was based on voluntariness.

Let’s return to the kick-off event. At this event, it was very important, especially at the very beginning, that the entire management team was present as a visible sign of the value and relevance awarded to the issue. Furthermore, the managers showed a great commitment to the idea and supported the aims of the initiative fully and very credibly. In order to make this possible, the team had sufficient time and opportunity to discuss and address the issue in advance. The two days that were taken for the kick-off event itself were no less important. They made it possible for the selected employees to address the topics themselves as well as deal with themselves as individuals and as a newly created group or community. Thus, most of the participants were enthused for the process they were facing, even if they had originally still been hesitant. Interactive, dialogue-oriented and emotionalizing elements as a frame as well as an agenda that was adapted to the immediate needs of the group contributed their part.

Then there followed a period of just under two months to develop ideas, pin down, adapt and work on the chosen topics, develop the group, engage and involve further colleagues, etc. The mentors chosen by the given initiatives themselves had the primary role of suppressing the typical management reflex during this time: neither taking responsibility, directing, probing or controlling, nor taking decisions for the initiative that could be taken by the group itself. The mentors were only supposed to offer support as a coach where required, as soon as the initiative’s ability to act was in danger. As the need was rarely voiced, this was on the one hand a simple task for most mentors, on the other hand there emerged uncertainty whether that was to be taken as a good or a bad sign. Quite understandable! All in all, several managers experienced this mentoring role as throughly new and unusual and therefore a personal challenge.

The first review workshop luckily showed that the trust, reticence and letting go had been justified and that most of the individual initiatives were »on track«. Despite a few difficulties, the employees were also still motivated. Upon questioning, and not really surprisingly, the greatest challenge had been to find the time for this additional task. One participant, however, added quite pragmatically that all initiatives had, though, delivered good interim results, after all. Quite! With the help of cooperative advice, several participants were able to receive specific support from colleagues and therefore profit from the knowledge and experience of the bridge people community. From the point of view of the process, it was particularly important that the individual members and groups were able to see each other as part of a committed and lively community on this day.

There followed a period of approximately three months to develop the own topics further. This time, the development was coupled with the task of establishing a decision memo for the second review workshop, which would then be used by the management team for their decision on what was to happen in each individual initiative in the future.

Unsurprisingly, curiosity once again rose among the management team in advance of the second review workshop: what will the outcome be? How hard or easy will it be to take the necessary decisions and what will we be facing with those decisions? Will we be able to consider the process so far a success? What will the bridge people think?

As soon as the workshop began, one thing became clear straight away: since the space for exhibition material ran out in no time, there was obviously no lack of commitment and motivation. The presentation of the results and the decisions to be made included creatively designed video statements (by two members who were unable to attend), functioning prototypes of potential new products, results of a comprehensive, Europe-wide questionnaire among colleagues on the topic of CSR, detailed process analyses, etc. One initiative had furthermore created stickers bearing the overall initiative’s logo and brought them as a present for everyone – this idea had, incidentally, emerged during the first review workshop.

All in all, the degree of commitment of show as well as the range and variety of results still had the power to surprise. Therefore, the voting (during which all attending participants had to vote for their own five top initiatives, results or suggestions) was not an easy task for most. Eventually, the management team entered the decisive round, taking the result of this voting with them, took the necessary decisions, passed resolutions on the future approach and presented these to the assembled community. Certain topics were to be passed on to the responsible line management, some were to be continued as classic projects, yet others in a more free form in what was called a »joker team«. Some groups were asked to make their suggestions more concrete or work them out further. Some were also rejected, with an appropriate justification. Participants had already announced in advance that »I will continue by topic anyway, even if I don’t (yet) get a ›GO‹ from the management team!« or that »If my topic will not get the green light, I can switch to one of the other initiatives!«. Yes, wonderful! This is the sort of ownership and commitment that organization developers and others like to see; after all, it is an essential condition for an enlivened and more dynamic company.

The CEO’s closing words at the end of the second review essentially remain a fitting conclusion:

It is amazing and very positively surprising what is possible in a short time. We trusted our people that they will do the right thing, we gave them the necessary space and let them do their thing. That fostered potentials.

Quite!

Thomas Meilinger

3. December 2014

You don’t have to look far to find instances of the world of VUCA. One of the most immediate examples are production supply processes: logistics. Volatile markets, uncertain conditions, complex production systems and ambiguous parameters for decision-making demand new skills.

You don’t have to look far to find instances of the world of VUCA. One of the most immediate examples are production supply processes: logistics. Volatile markets, uncertain conditions, complex production systems and ambiguous parameters for decision-making demand new skills.

A look at our clients reveals that an organization’s logistics sector is increasingly becoming its success factor. Logistics areas are growing disproportionately, transport costs are rising, client and delivery networks are becoming ever more global. Nevertheless, we still frequently encounter the notion that logistics are merely a service at the end of the process chain, not a driver at the spearhead of change.

In reality, we see that logistics has long since moved into the focus of top management. We have noticed a considerable increase in client requests for change accompaniment in logistics processes, particularly so in the automotive sector. Usually, they come together with a demand for qualification and the creation of logistics skills.

At SYNNECTA, a small group of experienced consultants have specialized in change management and logistics process training. Logistics projects put us at the exciting interface between the internal and external worlds, between client demands and delivery networks, between process optimization and plant harmonization. We see the trends of our society reflected in the logistics sectors of organizations: they are an indicator for change and future developments.

With the increasing concentration on key skills (make or buy) and resulting strategies to outsource, delivery chains are more and more frequently based on a division of labour. Sharp competition on global markets, short product life cycles and high client demand foster the steep rise in the number of derivative products: supply guarantees in combination with highly flexible delivery chains are moving into the focus of managerial decision-making.

Supply chain management has thus become an important component of an organization’s planning and management. Elements of logistics structures such as cross-docks, automatic small parts warehouses and tugger trains demand innovative processes, great investments and complex system landscapes as well as, importantly, behavioural change and entirely new standards of management. We have methodical answers:

- Insight images provide us with a view of the entire process chain and clearly depict its complexity.

- Planning games bring the reality of logistics into the seminar room and clarify, e.g., bull-whip effects and how best cost country sourcing and parts availability are related.

- Puzzles help develop an understanding for lean processes, value streams and line back principles.

- Defamiliarization opens up new points of view, networks create synergies.

- Complexity is not confused with complication; we respond with simplicity and standardization.

- SYNNECTA events formats pick up flow, pulse and rhythm.

- Logistics connect: we understand processes and we can do people.

Renate Standfest

More than 26 per cent of medical complaints registered in the EU are due to psychological disorders: they make up more incidences than heart disease and cancer. The greatest part of these 26 per cent are related to anxiety and depression.

More than 26 per cent of medical complaints registered in the EU are due to psychological disorders: they make up more incidences than heart disease and cancer. The greatest part of these 26 per cent are related to anxiety and depression.

Imagine you are an employee in a medium-sized business with a history. You are well connected within your organization, are considered creative or you are committed – ideally you are even all three of those things. You are still several levels from the top of the company hierarchy and at this point you are certainly not at the forefront of important, strategic projects.

Imagine you are an employee in a medium-sized business with a history. You are well connected within your organization, are considered creative or you are committed – ideally you are even all three of those things. You are still several levels from the top of the company hierarchy and at this point you are certainly not at the forefront of important, strategic projects.

You don’t have to look far to find instances of the world of VUCA. One of the most immediate examples are production supply processes: logistics. Volatile markets, uncertain conditions, complex production systems and ambiguous parameters for decision-making demand new skills.

You don’t have to look far to find instances of the world of VUCA. One of the most immediate examples are production supply processes: logistics. Volatile markets, uncertain conditions, complex production systems and ambiguous parameters for decision-making demand new skills.