12. September 2017

»Not yet an answer«

Consider a group of people. They are all different, not the same, but they have one thing in common: they work together. They were told that work these days needs agility, and diversity. Everyone nodded in agreement. All of them have the same education, know the rules and the goal. Yet cooperation simply won’t happen. They purchase new methods, from experts. Be different. Faster. More agile. Still, nobody understands what is to be done. Everybody does as they know. Until someone asks a question and listens well. That is new and different. The question asked for a meaning. That was inspiring. They notice that mindsets cannot be purchased. Agility and diversity also cannot be bought. They say, let’s ask some questions and listen well. While that is not really anything new, it has not yet been established everywhere.

Hanna Göhler

Picture: freepik.com

1. June 2017

Looking up at a starry sky, we might have a sense of sublime peace and magnitude or hear the music of the spheres. They are ways to look or hear into the sky; images we create for ourselves. Heinrich Hertz, as a hardcore natural scientist, noted that we create images of things for ourselves that contain but an indication, in order more or less to fulfil our desire for explanations and increase or range of options. Hertz thereby dissolves the bi-fold world view that juxtaposes »The world is fact and matter« with »The world is words and stories«: every insight, every image of reality is but a potential and only valid as long as it is useful and cannot be proved wrong. They are images that describe and order our experiences with the world. They change as soon as other perspectives appear to be more effective.

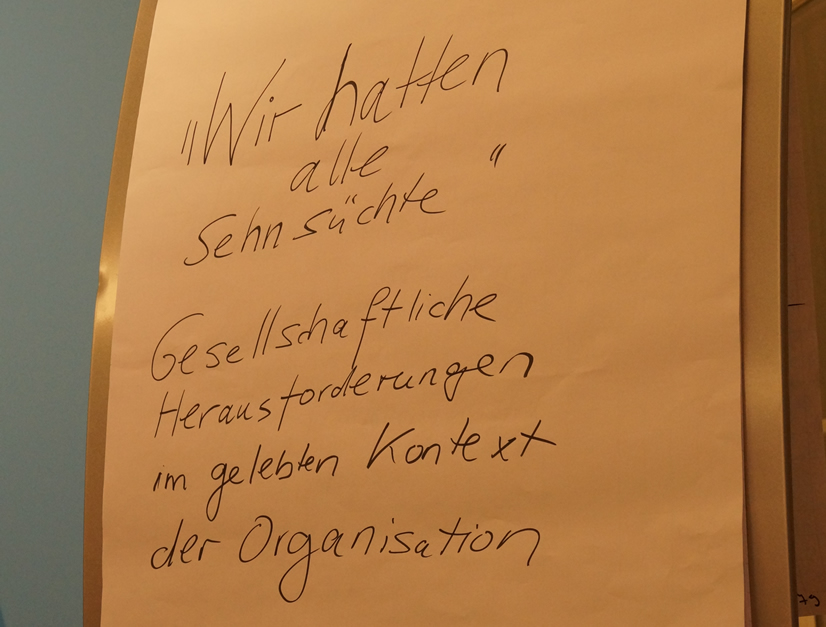

In organizational development, we are currently facing such a change. All image changes have a great impact on the behaviour and actions demanded of us. How can we describe this image change?

A first, very effective, dichotomy in the description of companies began with just one word: value-adding. Over night, attitudes changed: significant functions were no longer value-adding and their value became the support of value-adding fields. It was a reassessment that at the same time opened the doors to lean thinking. Generations of managers learned that the art of management was the reduction of effort and a consistent awareness of efficiency. The daily bread of leadership were costs and their reduction, development of ever leaner processes and their reproduction. Thus emerged an ‘image’ of leadership and excellent organization, as well as an unprecedented race for the lowest cost.

We are now experiencing a new dichotomy. This one can be summed up with the terminological pair agility/excellence (the euphemism for a radical lean concept). It separates the organization into two distinctively separate enterprises, on the one side a turnout or supply chain organization and on the other side the organization dealing with innovation, product and business models. The latter is described as agile, acts in smaller units, is close to the market. This second dichotomy has been explained with the push for digitalization, a reverse push for globalization, the transition to a knowledge society. We consider it a reaction to the expectation of non-linear events, which even smart data are blind to. To put it more fashionably: disruptivity. This ever more urgent expectation that something unforeseen will happen and redefine the game is causing companies to react with their goal to themselves be the source of disruption: to be innovative, or at least highly adaptive, i.e., to be agile.

Such a goal cannot be achieved in organizations with many hierarchical levels and with the classic European-American planning and strategic logic. It requires the introduction of incremental forms of work and planning, working with vision spaces and setting goals of wastefulness as well as cost and achievement. The difference within the second dichotomy is most apparent at hand of the meaning of mistakes. In the supply organization, mistakes were and are planning and process mistakes, they are an interruption of the well-controlled and must be eradicated immediately and for good.

In agile organizations, mistakes are a ladder that can lead to the new; they are a necessary part of flexible trials, which lead to new learning. The mistake leads to further understanding. Therefore, playing becomes a leading principle for agile organizations, which can resort to notions of the Classicist period, e.g. Friedrich Schiller’s remark that a human is only human, in full possession of his and her entire potential, at play. This »other« form and logic of work applies only, however, where the event is imminent or hoped-for. The supply chain organization still maintains the reliable logic of planning, process and standardization.

As organizational developers, we tend to pounce on the new, the second side of the dichotomy, and sometimes neglect that the first side of the dichotomy, the old, is and remains the basis. The psychological reactions we experience are similar to those we saw during the first dichotomy, the differentiation between value-adding and non-value-adding: feelings of devaluation on the one side and a powerful, euphoric narcissism on the other side.

What does that mean for us? We also need to match the support we offer to this dichotomy. What are the psychological, motivational needs of the supply chain organization? It will not be possible to alter the organizational units necessary for success into a culture that corresponds to Amazon warehouses or Apple’s Foxcom organization. Even in a radical lean concept, we will have to win the heads and hearts of the people. That is all the more true as employees are required to have a decidedly higher degree of education within industry 4.0. Next to flexible education concepts, which are available in combination with blended learning approaches, we believe that we need a powerful revitalization of Kaizen: after all, the crux of these approaches is not and was never the achieved savings potential, but their motivating power by the way they foster taking responsibility. Self-efficacy has to be possible even in these highly standardized workplaces. It would be a great mistake to undervalue the human factor in the supply chain organization for the sake of efficiency.

Both attention and money are currently being primarily fed into the agile parts of the organization – method training (scrum/design thinking) is flourishing as much as the trying of new organizational forms. Manifold questions on leadership of self-organized units, etc., are addressed and offers of support are developed for teams and relatively independent units such as, e.g., the »agile coach«. We see that it can be very enriching and pleasing to work in such relatively free teams, but that it is also exhausting and sometimes threatening to be in this form of social dynamic, devoid as it is of the protective character of leadership. Amid the plethora of supervision options, it is clear that a one-off team training will not suffice. Group dynamic is dynamic and it runs an irrational course, so we consider internal and external permanent supervision. Again, blended learning can provide an additional element of support.

At the same time, an agile form of working brings up a range of organizational questions. At first, these were limited to the transition from a project team to an agile team. By now, the entire organization needs to be considered: hierarchical levels become superfluous, a whole range of questions of control and transparency remain open, hence the unrest is manifold. Responsibility and freedom of action is to be moved to the edges of the organization, so that the organization is seen in its breadth rather than in the height of the pyramid.

We are beginning to learn how such organizations work and are lead. To boot, we expect that parts of organizations are hooked up to the business although they are not classically part of it – that complicates the task of the leadership even further. Is it enough to point out charismatic leaders, who are so very much in fashion in politics at the moment? Or do we need a more in-depth re-definition of leadership behaviour, an abstract and fragmented notion of which we can find in the concepts of transformational leadership?

We take a single aspect: agility – the description of an organization that acts flexibly, fast, with many ideas and taking responsibility – is only possible when the company lives the diversity of it own employees. That means that differences are not normatively blurred, but that instead the ‘otherness’ of difference is consistently addressed. This is the only way in which it can fulfil one of the great hopes that are connected with an agile organization: that it depicts the trends, expectations and movements in society within it and aids their understanding. That is the state a company striving to be innovative and highly adaptive aims for.

What is often underestimated is the effect on the companies of what we know as governance and service units – they will have to offer platforms in future that allow a range of units with a variety of support needs to hook up. This is a place of excellence that provides its own achievements to the agile units. These units need to free themselves from the constant discussion that they are not assertive enough and grow into becoming providers of auxiliary, also flexible, solutions.

Not least, an organization that is steadily ahead of itself in order to be able to be what it will need to be can remind us of the place an »enterprise« ought to have in societies. People have questions of meaning, people want to live in a context that does not tax their conscience – we are able to engage in much self-deceit in this matter. Yet there remains a basic standard: my organization should be a good place – and in an agile world, that should be true not only within the borders of the company, but in its manifold connections with societies.

Companies will therefore hardly be able to avoid the following questions again and again: why does society tolerate our striving for profit? What is it we provide that gives us the right to egotistical striving to profit? Pharmaceutical companies putting their money into the development of medicine for children know that that is not where the big profits are, but they can chose to do so because they have a duty – free to choose, but imperative in the absolute – to be of use to the whole. Looking into the world, are not the big corporations one of the few places where global questions are negotiated? Or when did you last hear the UN mentioned on the news?

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

2. June 2016

»A society that cannot bear old age will be destroyed by its own selfishness.« Willy Brandt

How old are you?

How old are you?

When I was six, I thought I was old – I was, after all, about to start school. When I was eighteen, I did not feel like an adult. And now? I feel young, middle-aged or old, depending on who is looking at me or talking to me. I might feel fresh or stale, experienced or inexperienced. Why is the dermatologist trying to sell me anti-wrinkle cream? I thought millennials were forever young?

Anyone who has been born has legal capacity. Be it school attendance, criminal accountability or the vote: age limits and thresholds mark particular stages in our biographies. Time, beginning, end, development, change. Our own age is just a simple number, but it brings with it a world of meanings. It is a social construct: there is a calendar age and a biological age. These denotations follow no natural necessity; they are social agreements that we have grown up with and which we often accept as given. We allow such definitions to shape our individual identity. Employee age also plays an important role for companies and in diversity management: consider child labour laws, childcare provision in family-friendly companies or retirement schemes. It is also relevant with regard to capacities, staffing, team composition, and every day in the way individual employees act around each other.

»Age« can mean any age. Each age has its own ascriptions. The terms »young« and »old« usually hide assumptions and stereotypes: for example, that young people have less experience or that older people are no longer flexible. As organizational consultants, we have to ask which kind of ascriptions, rules and norms are defining and shape an organizational culture. What does that mean for the working climate and the attainment and work processes? For companies with an international remit, we also have to ask how definitions of age and the corresponding expectations differ depending on and shaped by the culture and laws of a country.

»Nothing displays a person’s age as much as when they denigrate the young generation.« Hermann Hesse

In 2020, half the population in Germany will be over 50 years old. All generations need to consciously note this fact now, here and today and put it on their agendas. This is about ageing processes as well as the integration of different generations. Germany is ageing, but international migration combined with a shortage of specialists is bringing young generations into companies. This is not a hypothetical situation: it is happening right now. A holistic diversity management approach should therefore realistically address all generations and age groups. The entire workforce should be made aware of the fact that all employees can learn from each other. That is easier said than done.

It does not matter which category the diversity management is focused on: in company cultures where hierarchical career ladders, seniority principles and authority are part of the norm, the creation of a new awareness will require enormous changes in personal attitudes and daily interactions as well as in organizational structures. This concerns people of all ages.

In what way is age related to experience and ability? Here, I support a deconstructivist approach. Trust the (given) age and individuality of a person. Mentality and performance should be more decisive than an image I might have in my head of you or myself. PS: I will not use anti-wrinkle cream.

Hanna Göhler

25. February 2016

In Berlin, people are queueing up to see an exhibition comparing expressionist and impressionist painting. It is a very regulated experience of art: this is well established, known art. There will not be any exceeding challenges, irritations or surprises. Here, on the other hand, it is quiet and empty. Nobody knows yet what these sculptures and performances might have to say. These sculptures have not yet been classified and are on display without a commentary. The exhibition in Berlin puts the spotlight on something that is known and has been evaluated. We, on the other hand, are encountering something different here: openness and the undefined. We have to find our own position; there is no official interpretation to relieve us of having to have the courage of our own opinion. We have to give our own judgement.

Companies are nowadays almost desperately searching for innovation, vibrancy, creativity and agility. Such places as these here can show us the prerequisite: the ability to open up for something that has not yet been tested, which is definitely not »more of the same«: something provocatively different. Something that instigates conflict, causes uncertainty and that is risky to evaluate.

This kind of context allows for new experiences and may give way to new perspectives. These visits are a metaphor for companies. They demand some distance from the tried and tested. That is one of the reasons I love these places. Here, I can feel that I also have the right to stand in front of a sculpture and be utterly clueless as to what it might tell me. And to then go on to discover another one that opens up a new perspective.

What does that have to do with companies, you might ask. I still experience companies attempting to be transnational – often successfully so. Leadership is considered to be a globally defined behaviour, the approach is inclusive. Groups from a wide range of cultures are learning to apply this model behaviour. However, while companies may be transnational and culturally global, the markets are multinational and are in fact in the process of becoming even more »multi« and diverse again. Like the pieces of art in this space, they contain difference, surprise, strangeness and sometimes provocation.

In my extensive travels throughout Asia and my encounters with many people at work, I have learned that we need to concentrate more on »multi« than on »trans« or »mono«. By retreating into trusted knowledge and established patterns, we will never meet the diverse otherness of cultures and ways of life. Our introverted orientation will fail to direct us to the dynamics of our dazzlingly diverse world and its needs.

Let us return to innovation, agility, flexibility: in order to be able to create a culture of openness, one must expose oneself to the new and yet uninscribed and allow it into our midst. Of course there are things I do not understand, things that leave me clueless and looking for what I know – and yet at the same time I am aware that it is these very encounters with the »other than I« that give me an understanding of difference. I realize that it takes internal difference for us to be able to cope with the diversity of the outside, which requires vibrant and creative adaptation.

Rüdiger Müngersdorff

How old are you?

How old are you?